Thor, Theism & Theodicy

Spoilers abound, for those who care.

You’ve by now heard our recitations about our comics reading of the last decade or so. Hopefully you’re all reading Crossing Worlds. In any event, despite only occasional glances until recently in the Marvel direction, it’s hard not to get Thor. Cultural osmosis and the odd skim through the Thomas and Simonson back-issues (along with now two feature films) show off Thor as the crux of the Kirby-esque bleed between soap opera, space opera and old-fashioned Wagnerian spear-and-magic-helmet opera, a Ren-Fair champion known for being the symbolically resonant but not overly complex avatar of hitting nasties with a hammer.

Imagine then the shock when Jason Aaron’s backstory-lite Marvel NOW crack at the line placed our titular hero in the centre of a proficiently woven crime drama, drawing more of its beats from psychodramatic thriller or long-form noir yarn than from the psychedelic two-fisted narratives we expected.

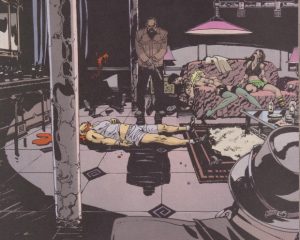

From the discovery of the first body, we are drawn into the story of the God-Butcher, the taunting and superior serial killer whose targets fit an epic profile, a brutal torturer and slaver unchecked through the systemic indifference and dysfunctionality of Marvel’s pantheons of deities. The story follows Thor as he haltingly, even reluctantly, investigates a string of killings across three eras. Aaron shares the narrative between the brash Thor worshiped by Vikings, the heroic modern Thor of the Avengers and the grand, scarred All-Father Thor from the End of Days.

Aaron has, of course, written one of the best crime dramas in comics’ history with Vertigo’s phenomenal Scalped, so his form is not in question. Thor, however, is more than just than a writer doing what he knows. Just as in Scalped, Aaron used the noir aesthetics and pacing to highlight and emphasise the Native American condition, here he uses the crime drama elements to explicate the contradictions within the idea of a the very idea of a ‘righteous warrior god’.

Surprisingly, the perfect training ground for considering the arc of faith and history

Surprisingly, the perfect training ground for considering the arc of faith and history

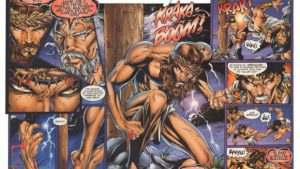

The run has narrowed in on what it means for Thor (and to Thor) to be a god. At the heart of this story is the excellent character work that Aaron, the master of the ensemble cast, has managed to devote to Thor as an individual. By introducing three Thors and developing few other characters past what is needed to carry the plot, Aaron allows his flair for comparing and contrasting the inner thoughts and feelings of a character to become laser-focused on the lightning god. In the early issues, we contrast Thor as a callow war-god leading men to their deaths with little concern for them as individuals (and, importantly, his followers seem equally unconcerned as to Thor’s motives as long as he answers their prayers for blood) contrasted with a considered Thor compassionately conducting the galactic equivalent of missionary work and reluctant to place his ally, Iron Man, in peril. By Issue #8, this circle has been closed as the younger god becomes the crippled soldier in the throes of PTSD, his sleepless nights haunted by horrors to which he was brashly blind until they struck, not his mortal worshippers, but himself. The only other character really drawn into sharp focus is Thor’s nemesis and ostensible villain, the aptly named “God-Butcher”.

Thor as a comic has generally had little if anything to do with actual Vikings – real, cheese-making, inglorious, piratical northmen – or, for that matter, any other aspect of human history or faith. In the world of mainstream comics “God” is either a term mumbled under a writer’s breath or said so often that semantic satiation kicks in, replacing any relationship with human worship or metaphysical wonder with a catch-all term for a power tier, like mutant or metahuman or the like (“The New Gods are under siege from the Elder Gods of the Godwall. Only the Godsword can shatter through the holy ranks of the Ninth Deific Legion!”).

On the other hand…actually, sometimes there are no words

On the other hand…actually, sometimes there are no words

Not so here. The comic’s tagline, “God of Thunder”, fits exceedingly well. Thor is a god, not just in the sense of his eternal backstage pass to Kirby’s lightshow of techno-shamanic power and might, but as reflected in the faces of his worshippers. His Vikings call on his aid and boldly claim his superiority over foreign gods. The exultant face of the alien child as Thor answers her prayers stands out. Esad Ribic manages to capture something in that face that is vanishingly rare in comics – worshipful adulation, intended to be seen as legitimate by characters and readers alike.

Why don’t Storm and Thor hang out more?

Why don’t Storm and Thor hang out more?

For once, it doesn’t feel like the worshiper is obliquely deferring to the reader’s preferred view on faith (the totally lame “Superman rescues the praying man in the dog-collar at his hour of need, you be the judge” story beat) or insincerely murmuring something about things “not dreamt of in your philosophy” as an excuse for not daring to interrogate faith or lack thereof in the context of the fiction’s shared universe. Instead, our protagonist is being full-throatedly worshipped (and condemned) and the Aaron/Ribic partnership has made this feel like the natural state of affairs.

Natural, however, does not mean right. There is a subtle moment, foreshadowing the manner in which Gorr’s hideous strength is itself derived from god-tech, where Thor casually describes Tony Stark as a god. This is surely meant to require reader response, priming us to confront the question of whether religion on 616-Earth is a cargo cult for the naïve, fooled by the economies of power built into the world of superhero soap opera.

This theme is then fully explored through the life of Gorr, the God-Butcher. Not just another generic ultra-monster equally suited to a boss-fight in the God of War games, Gorr’s life is portrayed as a perfect mirror to Thor’s own. Through Gorr’s eyes, Aaron is unafraid to wrestle with that ancient riddle, the theodicean Problem of Evil, crystallised around our culture’s current struggle to integrate freshly adamant and vocal strains of atheism.

No, he really doesn’t. It’s a valid question.

No, he really doesn’t. It’s a valid question.

Full disclosure: we’re both atheists. David is a Catholic so lapsed he can barely remember his Milton, and Robert was raised without religion, not knowing other people believed until he was around nine. Repeatedly burned by pop culture’s treatment of atheism, we were tentative, if not outright leery, of delving into this space. After the first nine issues of Thor, we’ve breathed a sigh of relief and can state with some confidence that the matter is in safe hands. Our villain’s descent to nihilistic madness has been carefully stage-managed and measured with wisdom and empathy. It is not Gorr’s atheism (or, more technically, anti-theism) that is condemned. Indeed, his honest, strong-willed rejection of the primitive shibboleths of his species is presented as his strongest, most heroic moment. Gorr is not presented as wrong in his criticism of the gods. Instead, we are presented with something that, whilst not condoning his ultimate methodologies, shows Thor’s growing awareness of his own culpability the culpability of those like him.

It is Gorr’s toxic despair, nihilism and self-righteous blindness that damn him (and all his victims) to the literal hell of his own creation. Gorr follows the traditional villain arc of devolving into what he hates – as he rains down his punishment on the just and unjust alike, it is Gorr’s very resemblance to an Old Testament apocalyptic tyrant that damns him, rather than his antinomian portfolio.

It is Thor who, through his trials, demonstrates the ability to develop a deeper relationship with his followers, his family and himself.

This is not as simple as an abnegation of his role to take up some sort of “path of humanity”. Rather, the work seems to indicate that, in the traditional Clarke’s Law technomagic fashion, Thor’s arc is to go beyond false god and secular Avenger towards a kind of spiritual singularity, a place in which adherence to fundamentally humanist ethics of empathy, service and sacrifice can serve to define what is admirable, and what is admirable can be shown as what should be worshipped and exalted.

Godliness, Aaron seems to suggest, is not a question of the power tier of hero or villain. Because the gods are metaphors for the human experience of dealing with power, Aaron recontextualises faith within the superhero setting as something part of that human experience rather than derived from an external, objective, source. By refusing to simply reject atheism as some form of failure to recognise the truth of the world around you, or as an indicator of inevitable moral decline, Aaron explicates that gods – be they real, false or metaphorical – are symbols, and that the traits they are ascribed say more about us then they do about them. By making the gods real people with personalities, Aaron demonstrates that it is not the whole of the god that is being worshiped, but the good within the god.

There seems to be an answer to the theodicean question writ between the lines – in the Marvel universe, power may not given to the deserving, but it is those who use their power in the service of compassion, humanity and above all else, humility that are worthy of our exaltation. Be they ‘god’ or ‘scientist’, it is figure of the superheroes – superheroes like Stark and the Avengers-era Thor – that are themselves mythic figures worthy of our supplication and invocation. In this modern mythology, it is the superhero who answers the prayers of the righteous and the meek. Thor, it seems, provides a thoroughly modern slant to Socrates’ famous answer to the question of what we should worship – we should worship the good, and not the powerful. Thor as we most commonly know him, the Thor of the Now, is in Issue #9 pushed by Gorr to admit that he sees the idleness of the Gods as woeful, when contrasted with the activities of his heroic mortal counterparts. Thor may well come to a refutation of the role of the “god who doubts”, but if he does so, we suspect that it will be based on the exaltation of the value of the symbol, without absolving anyone of the need to critically interrogate those who claim that responsibility.

As a comic, we can’t pretend Thor is without some downsides, of course. The premise is so powerfully sketched in the first issue that you have to wonder if the arc thereafter isn’t a little too decompressed. The second and third issue are largely explication of what was already implied, and it isn’t until Issue #5 that the comic really gains momentum once more.

If one is being fair, it is probably also important to note that Aaron’s run isn’t the first Thor comic in recent days to take advantage of the Thunderer’s extensive lifespan by setting the story within a trinity of eras. By all accounts, and with no comment as to comparative quality, Ultimate Thor used a similar technique not very long ago at all. Less recent converts to Asgardian scholarship may well be able to give us other examples.

Still, these are minor niggles at most. These comics stand as exemplars of everything Marvel NOW promised – solid stories about classic characters, unburdened by the navel-gazing infecting the comics industry, such as the need to retell belaboured origin stories, sync with cinematic counter-parts or acrobatically leap mega-events and continuity hurdles. It starts off what we hope will be a long and successful stewardship of the character, what we have come to expect as Aaron fans, and now, solidly Thor fans to boot.

So does the comic, in the final analysis, solve the Problem of Evil? Well, not in the first nine issues – but it’s a tall order to ask any piece of writing to answer a question that theologians and philosophers have been grappling with since time immemorial. What it does is provide a compelling paean to both the strengths and weaknesses of gods as a concept, calling for us to reject on one hand bitterness and bleak nihilism and on the other asking us to look for a higher good than blind faith.