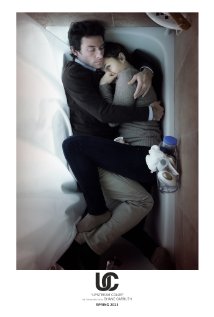

Movie Review: Upstream Color (2013)

“Hinju gokan” (“Guest and host interchange.”) – Zen Kōan

“The kōan is both the object being sought and the relentless seeking itself” – Victor Hori

Upstream Color is a zen kōan captured on film. Beautiful, elusive, utterly open and closed all at once, it invites contemplation of meaning on multiple levels – and that contemplation is both the film’s subject and its purpose.

You don’t want to know much about Upstream Color‘s plot before you see it (and you should see it) – not because that plot will BLOW YOUR MIND, but because your experience of the film should be a discovery that’s shared with the film’s characters. Suffice it to say that the plot involves a man and a woman who have been deeply damaged by similar traumatic experiences, and the film explores the relationship that they build together in the aftermath of that damage.

Some of you may have heard that the film is “difficult.” You might think that reading about the film’s plot beforehand will help you process it as you watch it. I submit that reading a synopsis will not help prepare you for Upstream Color in any real sense, but it may very well diminish your experience with it.

The good news for you is that you don’t have to worry about “understanding” the film the first time around in order to find real worth in it as an emotional, sensory experience. Like a kōan, you can receive it without necessarily grasping it whole. Like a kōan, Upstream Color is both meaning to be sought and the relentless seeking itself. That might sound ridiculous (it does!) but it also feels right.

The better news for you is that unlike Carruth’s first film, Primer, Upstream Color ultimately isn’t all that difficult to grasp in terms of its plot mechanics – at least, it wasn’t for me (your mileage may vary). The film demands engagement and a willingness to make mental leaps, but this isn’t a film that requires multiple viewings in order to know its essential contours and to grasp at its “meaning” despite the abstract nature of the narrative. In Upstream Color, abstraction of the narrative doesn’t diffuse possible meaning, it intensifies that meaning. At heart, Upstream Color isn’t complicated, but it is complex[1].

In Primer, Carruth fractured the narrative and created confusion and dislocation in an effort to convey both the disorientation of time travel and the feeling that comes when there’s a disintegration of trust in a relationship.

Carruth uses fractured narrative and conscious ambiguity in Upstream Color in order to convey the fractured and ambiguous state of his characters’ identities. This approach might feel gimmicky if Carruth didn’t commit so resolutely and fearlessly; if he didn’t wield his obvious intelligence with precision and care in order to graft layers of emotional resonance onto essentially aesthetic choices until the divide between them is obliterated.

You can make the argument that Carruth seems less comfortable/capable dealing with emotional throughlines than he is with giving the audience a Rorschach-y pattern of behavior that we can then project onto; that Carruth’s clinical approach to filmmaking leaves the emotional core of this film suggested rather than felt. You can roll your eyes at the “flowers/worms/pigs/flowers” cycle that Carruth invents for the film, and/or argue that this cycle, and the inclusion of Thoreau’s Walden into the proceedings, strains for a profundity the film doesn’t quite earn outside of its aesthetics. You can assert that it’s not as magnetic a film as Primer, and that it has significantly less re-watchability than Carruth’s first effort. Some will assert these things, and while I’d argue with some of these points, I’ll concede that they’re arguments worth having.

But what should ultimately matter, I think, is whether the experience moves you; whether you take away more than what you came in with – provoked to thought. Upstream Color moved me. It provoked thought and internal debate, and this review/reflection. That makes it a success in my eyes, and a film that people should seek out in order to be challenged and (potentially) moved as well. A portrait of addiction, an inquest into trauma, a rumination on nature’s cycles, a character study, and a riff on Walden, all wrapped up in a big, ominous bow, Upstream Color is a thoroughly unique film and well worth contemplating. This is the sort of deeply ambitious, wonderfully idiosyncratic filmmaking that is all too rare these days, and fans of film should make it their business to support that.

That’s the review, and it’s all you need to know whether you’ll seek Upstream Color out or not. The film will be released May 7th on DVD, and you can buy it any number of places. What follows now is a brief examination of the film. It isn’t critical, it’s exploratory, and it spoils the hell out of the movie (well, more accurately it spoils the architecture behind the film’s story, and I’m convinced that you don’t want to understand that architecture beforehand. Bookmark this page until you’ve seen the film, then come back and share in my twitterpated musings).

…Seriously. Don’t read this until you’ve seen the film.

At the heart of Upstream Color is a relatively “simple” cycle: Flowers are exposed to a mysterious substance and turn blue in color. They are uprooted by unidentified people and brought to a nursery. At the nursery, these flowers secrete a powdery substance on their leaves that may be turned into a street drug. The grubs that live in the soil around the roots are exposed to this substance, and by pouring liquid over the grubs and drinking the liquid you can attain a kind of eerie synchronicity with others who also drink the same liquid. If you ingest a live grub whole you become intensely susceptible to suggestion.

A shady dealer/thief (referred to, aptly, as The Thief in the film’s credits) who appears to work at the nursery uses these grubs as a means to steal from people – forcing them, disturbingly, to ingest the grub and then instituting a hypnotic regimen where he has them empty their bank accounts and give over everything of value to him. Afterward, he releases these people back into their lives with no memory of what’s happened to them.

A second enigmatic person (referred to only as The Sampler in the film’s credits) uses sound in order to draw the victims of the Thief to him. He removes the grubs (now long, Cronenbergian worms) from their bodies without explanation and transfers the worms into the bodies of…pigs[2].

The pigs then carry a “link” of sorts, seemingly psychic in nature, to the person that the worms originally inhabited. In turn, that person is also somehow linked to the pig that’s hosting their parasite (see the quote that opens this review: “Guest and host interchange”). By being near the pigs The Sampler can effectively “listen in” on that person’s life. At a certain point, certain pigs are selected to die. Those pigs are placed in a bag and dropped into the river, where they eventually drift downstream and rot – releasing a mysterious substance that will be absorbed into the nearby trees, turning their flowers blue. These flowers are uprooted in the wild and brought to a nursery…. Cycle complete.

The details of that cycle are really the only “mystery” in Upstream Color, and spelled out this way they might seem somewhat mundane, and perhaps silly. But in Carruth’s hands, as experienced in the cinema, this cycle takes on a kind of magisterial power, and what could be a fairly simplistic message (“we are all, like, connected…maaaaaaaaaan”) becomes something eerily resonant because of how Carruth decides to frame and display that cycle to us, the audience.

“…kōan after kōan explores the theme of nonduality. Hakuin’s well-known kōan, ‘Two hands clap and there is a sound, what is the sound of one hand?’ is clearly about two and one. The kōan asks, you know what duality is, now what is nonduality?…” – The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, edited by Steven Heine

“Hana o mite, hana mo miru” (“Look at the flower and the flower also looks.”) – Zen Kōan

That message of “Non-duality” is a major theme of Carruth’s film. Boiled to its essence, “non-duality” is “interconnectedness,” a “primordial, natural awareness without subject or object.” The concept of circular interconnection is threaded throughout Upstream Color in ways large (see: the flowers/worms/pigs cycle) and small (see: the daisy chains that Kris and Jeff create out of excerpts from Walden, a book that is in part about connection). Metaphorically speaking, Jeff and Kris “look at the flower and the flower also looks.” This idea of is literalized in the film to the point that, at one point, neither Kris nor Jeff nor the audience can know whose memories are whose.

Upstream Color‘s arguable strength as an experience is drawn from the ways in which a “simple” theme of non-duality is explored relentlessly and with fearsome, questing intelligence. In Carruth’s hands the notion of interconnectedness is as sinister as it is potentially enlightening, and not at all simplistic. Interconnectedness isn’t simply something hippie-ish to be sought, it’s also something mysterious, frightening, and open to abuse. The existence of something that can bring about and literalize this primordial awareness in a near-spiritual sense is corrupted on several levels by people who see only a means to play or to exploit and manipulate – as eerie a metaphor for emotional abuse and manipulation as I’ve seen. The film raises questions that disturb even as they stir us: Do Kris and Jeff really feel drawn to each other? Are they acting on impulses that aren’t even their own? Did Jeff really fall into addiction, or is this a narrative he’s created to explain his degradation at the hands of the Thief?

And on that note, for this viewer, perhaps the strongest and most effective metaphor conjured by the film is one of addiction/trauma and recovery. Carruth gives viewers several glimpses of how the compound created in nature is refined/exploited/altered in order to become a kind of narcotic, going so far as to show the Thief character peddling pills derived from that compound, and having the character of Jeff identify as an addict at one point in the film. Kris’s behavior while under the influence of the Thief and his Cronenbergian worm-things is classic addict behavior – detaching from her former life, not needing food or sleep for long periods of time, selling off things of value, raiding the fridge in sudden hunger and thirst, revulsion at her own body and what she has become, helplessness in the face of it. It’s easy to see Kris’ attempt to cut the worms from her body as an example of the kind of self-harm that self-loathing addicts can engage in, and/or an attempt to free herself from the demons of addiction[3].

…And now, a word (or two, or more) on Walden:

“All change is a miracle to contemplate; but it is a miracle which is taking place every instant. Confucius said, “To know that we know what we know, and that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge.'” – Walden, Thoreau

As many have already pointed out, and as should be obvious to anyone who watches the film, Walden figures heavily in Upstream Color. While there’s likely much to be said about the ways in which Thoreau’s book reflects and contrasts Carruth’s narrative, I was far more interested in the ways in which Carruth’s use of Walden feels autobiographically driven.

As a viewer with a degree of knowledge about Shane Carruth’s career thus far, Walden‘s presence in Upstream Color feels revealing. Carruth read the book which focuses, among other things, on topics like self-reliance and economy of living, after self-producing/etc his first film, Primer. As a filmmaker, Carruth is a transient – living from place to place, without health insurance. The project he intended to be his follow up to Primer – an ambitious sci-fi story called A Topiary – never happened for funding reasons. Those years of his life were “lost,” “wasted” by Carruth’s own admission, and the filmmaker became doggedly self-reliant once more to get Upstream Color up and running.

All of this stuff – the stripping away of the past and the need to reinvent yourself in that aftermath, the examination of self-reliance, the economy of living – all of this was deeply relevant in Carruth’s life, and to Thoreau’s text. As seen through this lens, Upstream Color feels deeply personal – as though Carruth is exploring his own interior landscape through the medium of the movie, creating something quasi-autobiographical in theme. The idea of having a part of your life taken from you inexplicably, and needing to rebuild yourself and your sense of who you are, feels like a direct outgrowth of Carruth’s own experiences, and his use of Walden in the film highlights this sense of quasi-autobiography.

That wraps up my initial, rambling thoughts. Have you seen Upstream Color? Why not share your own initial, rambling thoughts with me in the comments?

April 26, 2013

Fantastic write-up. After our screening ended, my friend and I talked for almost 3 hours trying to dipher the movie (This fact would please Carruth, I’m sure). Very much looking forward to seeing it again; it went by in such a rush of images and ideas that I’m sure I missed several points, but I think we got the gist of it. Many questions I’m still thinking about, though.

* Did you think the Thief, the Sampler, and the Flower Women were all in cahoots in the scheme, contributing to and manipulating the cycle? The women certainly seem harmless, and the Thief could simply work at their nursery (which I missed completely the first time). But I’m still utterly mystified at how Kris ended up at the Sampler’s farm, unless she was ‘programmed’ by the Thief to do so. This implies at the very least, a connection between the Thief & the Sampler, to keep the cycle going.

However, I read an interview with Carruth where he says the 3 (Thief, Sampler, Women) are all working independently and unaware of each other. He said you could debate the level of the Sampler’s culpability in what the Thief did, but heavily implied Kris came to the wrong conclusion and killed the wrong man.

So, a natural question is: should we accept that explanation or not? Carruth appears to be the first to admit that his work is for others to unravel and dicipher, but this reminds me of Richard Kelly’s explanations of Donnie Darko that seemed completely at odds from what actually appeared in his film.

* Is it your understanding that the pig that was sacked and drowned was Jeff’s avatar? I couldn’t tell if we were meant to assume this via the juxtaposition of (a) the pig being dumped and (b)Jeff dropping his box of papers after being fired. Otherwise, I couldn’t distinguish the pigs enough to tell.

Great piece, again. So much to unpack.

May 6, 2013

Andrew,

I don’t know why I wasn’t notified that you’d commented, but I’m grateful that you did, and wanted to answer your questions as best I can!

(1) ” Did you think the Thief, the Sampler, and the Flower Women were all in cahoots in the scheme, contributing to and manipulating the cycle?”

No. I thought that they were independent of each other, and that their lack of awareness of one another really emphasized the idea of non-duality/interconnection. These separate, unsuspecting individuals are part of a larger “cycle” without even being aware of it. I wasn’t aware of Carruth’s thoughts on the subject, but I’m of the opinion that art is meant to be interpreted, and am a fairly big believer in “the death of the author” in terms of discussing/judging artistic work. That said, I also think artist viewpoints and intentions can be absolutely fascinating, as should be obvious here, given my thoughts on Walden in the context of this film.

I think that you can definitely debate The Sampler’s culpability – he’s living a vicarious life through others without their consent and by means of the horrible acts of others.

(2) “Is it your understanding that the pig that was sacked and drowned was Jeff’s avatar? I couldn’t tell if we were meant to assume this via the juxtaposition of (a) the pig being dumped and (b)Jeff dropping his box of papers after being fired. Otherwise, I couldn’t distinguish the pigs enough to tell.”

First off, I love that this is a legit question. Taken out of context IT IS BIZARRE. in context, I admit that I have no idea. It is certainly possible that the “sacked pig” and “sacked” Jeff were the connected parties. It’s also possible that it was Kris’s pig who died, post giving birth, and that the dropping of jeff’s boxes was a signal that the eerie connection between them had been suddenly severed as a result of the death of Kris’s pig.

What do you think?

Those are excellent questions, and I thank you sincerely for taking the time to read my ramblings!