Okay, heads-up: This article has three things known to be disliked by The Internet. The first is Doctor Who spoilers, albeit two-year-old ones. The second is some potentially upsetting imagery from my time working at a psych hospital. The third is length. It’s pretty long. Fair warning.

Steven Moffat recently apologized in an interview for rewriting the Time War on Doctor Who, undoing The Doctor’s actions and absolving his guilt. I really hope he means it. The Doctor means a lot of different things to a lot of different people, but The Doctor’s guilt over the Time War meant a lot to me in particular. This story is a bit of a confessional, but it’s also a testament to why The Doctor is important, and what he can do.

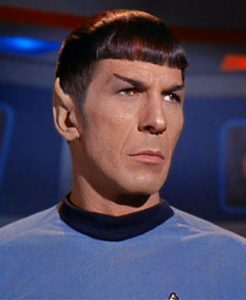

When I was a kid, I moved around a lot. My father’s job rendered him itinerant, and it meant a new city every three or four years. Not as much as an Army Brat, but not a lot of time to get settled into friendships before packing up, either. One of my favorite movies as a kid was Pete’s Dragon. I love that heartbreaking moment when Elliot flies away at the end, because Pete doesn’t need him anymore, and someone else does. We all make narratives out of our lives, I think, to try and help them make sense. This was mine, then — maybe I was going where I was needed. I tried as hard as I could, everywhere I found myself, to do the right thing, to be there for as many people as I could. I developed a taste for travel, an ease with opening up to people quickly, and a deep desire to see the best in everyone that I encountered. Still, I was a little…off. I was a studious kid, and I didn’t have a good handle on how to talk to people my own age. My heroes were always the brainy outsiders – Donatello, Spock, Data. Looking back, I wish that I’d had The Doctor then.

When I was a kid, I moved around a lot. My father’s job rendered him itinerant, and it meant a new city every three or four years. Not as much as an Army Brat, but not a lot of time to get settled into friendships before packing up, either. One of my favorite movies as a kid was Pete’s Dragon. I love that heartbreaking moment when Elliot flies away at the end, because Pete doesn’t need him anymore, and someone else does. We all make narratives out of our lives, I think, to try and help them make sense. This was mine, then — maybe I was going where I was needed. I tried as hard as I could, everywhere I found myself, to do the right thing, to be there for as many people as I could. I developed a taste for travel, an ease with opening up to people quickly, and a deep desire to see the best in everyone that I encountered. Still, I was a little…off. I was a studious kid, and I didn’t have a good handle on how to talk to people my own age. My heroes were always the brainy outsiders – Donatello, Spock, Data. Looking back, I wish that I’d had The Doctor then.

After college, my wife and I married, and headed off to a new city so she could attend grad school. My optimistic tendencies had led me to a psychology degree, and the psych degree led me to a job at a local psychiatric hospital to help put her through school.

At first I thought that maybe I wasn’t cut out for the business. I learned later that the place I’d made my employer was notorious for placing patients in danger to cut costs. A psychiatrist friend from a local hospital told me that when they thought their psych patients were faking it for three meals and a cot, they sent them to us to scare them out of doing it again.

I changed. I became the kind of person that you have to become to handle a place like that. I’ve seen things that I will never forget, done things that I’ll never forgive myself for. I’ve had conversations with people who’ve set themselves on fire. I removed a veteran’s prosthesis to search for contraband on a patient intake, and saw the heartbreak in his eyes as he removed his leg for an unshaven stranger half his age and wondered how his life had led him to that point. I saw my colleagues bludgeoned and stabbed, and was there when management asked them if they could finish their shift before going to the hospital. I can look at someone sleep, and I can tell you with all too much accuracy whether they’re a survivor of sexual assault. Everything that I thought I was came out of that place different. No part of my identity went unquestioned, no part of the world seemed safe. I barely ate or slept. I’d place myself in danger to enforce draconian policies, only to have those policies change two weeks later and learn that the way we were doing things before wasn’t legal. The realization that the people I was enduring this for were not good people nearly destroyed me.

I changed. I became the kind of person that you have to become to handle a place like that. I’ve seen things that I will never forget, done things that I’ll never forgive myself for. I’ve had conversations with people who’ve set themselves on fire. I removed a veteran’s prosthesis to search for contraband on a patient intake, and saw the heartbreak in his eyes as he removed his leg for an unshaven stranger half his age and wondered how his life had led him to that point. I saw my colleagues bludgeoned and stabbed, and was there when management asked them if they could finish their shift before going to the hospital. I can look at someone sleep, and I can tell you with all too much accuracy whether they’re a survivor of sexual assault. Everything that I thought I was came out of that place different. No part of my identity went unquestioned, no part of the world seemed safe. I barely ate or slept. I’d place myself in danger to enforce draconian policies, only to have those policies change two weeks later and learn that the way we were doing things before wasn’t legal. The realization that the people I was enduring this for were not good people nearly destroyed me.

The place eventually closed for repairs after an incident. (One that didn’t happen on my shift, and is a whole other story.) As they rebuilt and I was on leave, I pulled myself far enough out of my depression to start over. My wife and I moved closer to home. I went back to school, for music this time. Made new friends, learned new skills, struggled to keep my past behind me and focus on how wonderful my new surroundings were.

It was at this point that I finally broke down and listened to my friends who were clamoring for me to get into Doctor Who. I’d been hearing about it for about six years at this point, and being my sarcastic self, I said, “Sure, I’ll watch Doctor Who…from the beginning.” And I did. It started as a joke. Then it became an endurance contest. And at some point, a switch flipped and I got it. (Or I developed Stockholm Syndrome over it, one or the other.) I cried when the First Doctor left Susan on Earth. I fell in love with Patrick Troughton’s performance, and I cried again as he begged the Time Lords not to destroy him. I listened to Jon Pertwee describe how the beauty of a single flower changed his entire world. I slogged through plenty of filler, but I also started to recover something. That kid, that odd little kid who traveled and tried to help people and looked for the best in everyone — I started to see him again, in fits and starts. I thought about The Doctor’s travels, and about my own. I worried that something had changed for me. What if I wasn’t running to, anymore? What if I was running from?

You probably see where this is going.

After about three years and 700 episodes of Doctor Who running behind every load of laundry, every stint on a treadmill, every spare second I could grab, I finished the Paul McGann movie, and I started in on Eccleston. And suddenly I saw myself. The Doctor now, he didn’t know if he was running to or from, either. And the generosity of spirit that defined him was still there, but sadness was there now, too, just behind the eyes. He was weary. There was a hint of desperation in his drive to try the next new thing. There was a touch of sorrow undermining every moment where he came out on top. “Just this once, everybody lives!”

After about three years and 700 episodes of Doctor Who running behind every load of laundry, every stint on a treadmill, every spare second I could grab, I finished the Paul McGann movie, and I started in on Eccleston. And suddenly I saw myself. The Doctor now, he didn’t know if he was running to or from, either. And the generosity of spirit that defined him was still there, but sadness was there now, too, just behind the eyes. He was weary. There was a hint of desperation in his drive to try the next new thing. There was a touch of sorrow undermining every moment where he came out on top. “Just this once, everybody lives!”

Tennant took it and ran even further. His grief came in shades, tinted by love or anger or regret, but it was always there, fueling the fire and ice and rage. Tennant’s Doctor has long lost patience with the ugly things in the world. “I used to have so much mercy.” His disappointment was split between the evils that he encountered, and his own weariness with them. Eccleston’s Doctor was torn between running away from his past and atoning for it. Tennant’s was nearly 100% in the latter column. I started wondering where that part of the story was going, what they could do with it. You don’t see a lot of sci-fi heroes deal with PTSD, Iron Man 3 aside. And just as we craft stories out of our lives, we look to other stories to help parse them. I myself had been torn for some time between running away and atonement. I’d built a new life, but the old one still showed through the cracks if I slowed down for too long. I began to wonder whether any insight into making peace with yourself could come from this show that had already touched me so deeply, and touched upon so much that was troubling my soul.

Tennant took it and ran even further. His grief came in shades, tinted by love or anger or regret, but it was always there, fueling the fire and ice and rage. Tennant’s Doctor has long lost patience with the ugly things in the world. “I used to have so much mercy.” His disappointment was split between the evils that he encountered, and his own weariness with them. Eccleston’s Doctor was torn between running away from his past and atoning for it. Tennant’s was nearly 100% in the latter column. I started wondering where that part of the story was going, what they could do with it. You don’t see a lot of sci-fi heroes deal with PTSD, Iron Man 3 aside. And just as we craft stories out of our lives, we look to other stories to help parse them. I myself had been torn for some time between running away and atonement. I’d built a new life, but the old one still showed through the cracks if I slowed down for too long. I began to wonder whether any insight into making peace with yourself could come from this show that had already touched me so deeply, and touched upon so much that was troubling my soul.

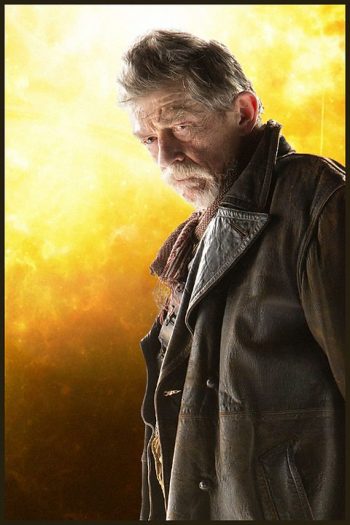

The through-line about the Time War seemed to take a bit of a back seat when Smith and Moffat came aboard. Much was made of Smith being the last of his species, but there wasn’t as much mention as to how that came to be. Smith’s Doctor downplayed it, avoided it, changed the subject – he was running away, more clearly than anyone had. As I worked my way through Smith’s seasons, it became apparent from both the show’s hints and my friends who had already seen it that the 50th Anniversary Special dealt directly with the Time War. They introduced John Hurt as an incarnation of The Doctor that the others were so ashamed of, they didn’t dare mention him. Now that resonated with me – closing off a part of your past so completely that it’s like a different person did those things. I’m embarrassed at how excited I felt, but I was so desperate for anything to tell me that it was okay, or to hint at how to make it alright. In the end it’s probably my fault, really, for expecting so much. But I wouldn’t have if the show hadn’t given me so much already.

I sat down to watch ”The Day of the Doctor,” and was crushed when it ended the way all of Moffat’s Doctor Who stories end. The Doctor waves his magic wand and everything falls into place and works perfectly, because of course it does, he’s The Doctor and he’s the biggest badass there ever was and the rest of the universe falls in line behind him. Moffat wasted a 50th anniversary and a stellar performance by John Hurt to tell one more story where The Doctor just magically makes everything better – SO MUCH BETTER, in point of fact, that he literally undid the tragedy that his predecessor caused. The War Doctor wiped out two entire species, except no he really didn’t, it’s okay now. He doesn’t remember fixing it, so he still has to be sad in the episodes you already watched, but from now on our hero can traipse about, his heart completely unencumbered by inconveniences like destroying two civilizations. It looked cool, but it didn’t mean anything. There was no emotional resolution, no coming to grips with what he’d done; he just wiped it all away. For those of us here on Earth, that’s not an option. And I know that my unique circumstances led me to want something really particular from the story, but I can’t be the only one who wanted something with more emotional punch than “making the thing go away.”

I sat down to watch ”The Day of the Doctor,” and was crushed when it ended the way all of Moffat’s Doctor Who stories end. The Doctor waves his magic wand and everything falls into place and works perfectly, because of course it does, he’s The Doctor and he’s the biggest badass there ever was and the rest of the universe falls in line behind him. Moffat wasted a 50th anniversary and a stellar performance by John Hurt to tell one more story where The Doctor just magically makes everything better – SO MUCH BETTER, in point of fact, that he literally undid the tragedy that his predecessor caused. The War Doctor wiped out two entire species, except no he really didn’t, it’s okay now. He doesn’t remember fixing it, so he still has to be sad in the episodes you already watched, but from now on our hero can traipse about, his heart completely unencumbered by inconveniences like destroying two civilizations. It looked cool, but it didn’t mean anything. There was no emotional resolution, no coming to grips with what he’d done; he just wiped it all away. For those of us here on Earth, that’s not an option. And I know that my unique circumstances led me to want something really particular from the story, but I can’t be the only one who wanted something with more emotional punch than “making the thing go away.”

Part of any story’s strength is in its ability to mirror our own struggles. It’s why the Hero’s Journey is such an enduring meme. (In the Jungian sense, not the cat picture sense.) We want to know that we can overcome the Bad Things in our life. The Doctor’s struggle for redemption meant something to me. When he let someone down – when he lost a Jenny or a Donna – we knew that his grief was compounded by the failures of his past. It added real emotional stakes to a traveler who previously was poking around in the name of sheer curiosity as much as a sense of justice.

Part of what makes the story of The Doctor resonate with so many is not just that he’s the smartest person in the room, it’s that for all of his bluster, he cares deeply about everyone that he meets – everyone there is, even, in all of time and space, whether he’s met them or not. It’s why he takes people under his wing, nurtures them, helps them to be the best version of themselves. It’s why he bristles at guns and spends as much time fighting with UNIT brass as he does advising them. Neil Gaiman once summed it up perfectly: ” A lot of our heroes depress me. But you know, when they made this particular hero, they didn’t give him a gun, they gave him a screwdriver to fix things. They didn’t give him a tank or a warship or an X-wing fighter, they gave him a call box from which you can call for help. And they didn’t give him a superpower or pointy ears or a heat ray…they gave him two hearts. And that’s an extraordinary thing. There will never come a time when we don’t need a hero like the Doctor.”

Part of what makes the story of The Doctor resonate with so many is not just that he’s the smartest person in the room, it’s that for all of his bluster, he cares deeply about everyone that he meets – everyone there is, even, in all of time and space, whether he’s met them or not. It’s why he takes people under his wing, nurtures them, helps them to be the best version of themselves. It’s why he bristles at guns and spends as much time fighting with UNIT brass as he does advising them. Neil Gaiman once summed it up perfectly: ” A lot of our heroes depress me. But you know, when they made this particular hero, they didn’t give him a gun, they gave him a screwdriver to fix things. They didn’t give him a tank or a warship or an X-wing fighter, they gave him a call box from which you can call for help. And they didn’t give him a superpower or pointy ears or a heat ray…they gave him two hearts. And that’s an extraordinary thing. There will never come a time when we don’t need a hero like the Doctor.”

The Doctor is about love. His journey is a fundamentally emotional one. That journey for the first eight years of the revived show was about him trying to redeem himself, to come to peace with a person that he used to be and a thing that he did that he couldn’t take back. But then he got to take it back, and we all lost a little something. Some of us more than others, maybe. But Moffat’s right. He made the wrong call.

June 3, 2015

Garrett, this was beautiful. Thank you for expressing it with so much honesty.