Interview with Joe Abercrombie – On Being Adapted To Comics

David here, Nerdspanners!

Joe Abercrombie is one of the decade’s most outstanding fantasy writers. Robert and I have both been captive devotees since The Blade Itself, the first of his award-winning initial series First Law Trilogy, hit shelves in 2006. Since then, his second-world fantasy setting has been the star of six books and a few short stories, and a further trilogy depicting the mud, blood, and betrayal common to his world, and the very real human motivations behind them, has been announced.

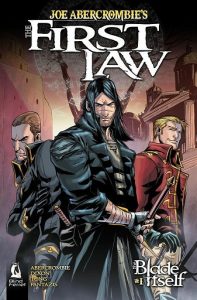

Now, we discover that everything old is new again with a story issued for our particular arena – The Blade Itself.

Or more precisely, The First Law #1: The Blade Itself – a full-colour comic book adaption of the work written by Chuck Dixon (The Hobbit, Robin, Moon Knight) and art by Andie Tong (Wheel of Time, Tron: Betrayal, TMNT). The comic will be available digitally and in trade and, best of all, the thing is going online for free. Already, over a dozen pages starring Logen Ninefingers, the thinking man’s barbarian, and Glokta, war hero-turned-Inquisitor, are up.

For those not familiar with Abercrombie’s work, he builds compelling stories that straddle the line between low and high fantasy, at once both utterly fantastical and anything but escapist, bringing a complex moral sensibility to a genre which has a reputation for being polemic and thematically repetitive.

Abercrombie’s immortal wizards, scarred warriors, and destined youths are well-informed by the genres they grow out of and critique, often skewing or plain inverting the archetypes not only as a comment on the fantasy genre itself, but as a sterling exemplar of the genre’s ability to reflect on our very real relationships with violence, warfare, barbarity, and civilisation.

With visually distinct protagonists and adversaries, plenty of dynamic violence and a facility for tight one-liners, it is easy to see why Joe Abercrombie’s First Law Trilogy is a great candidate for adaptation to comic book form. Chuck Dixon, known as an early adopter in the race from four-colour superheroics down to the grim street vigilantes of the 90s, stands as a solid choice for interpreting the material, and Andie Tong’s art for the Wheel of Time comics shows his strength in bringing a written descriptions to vivid life.

It is also equally easy to see just how massive a challenge the team has before them. Will Abercrombie’s subtle characterisation and political complexity carry over to into Dixon’s pages? Does the surprisingly handsome Logen and hearty Glotka from the first issue hint at a prettier, less unconventional style? Should we expect a more summer blockbuster view of violence to go with the more visual comic format, or will the team risk marketing only to the strong of stomach?

Robert had the opportunity to sit down with him recently and ask him some of our questions about the announcement, the comic, the adaption process and the fantasy genre.

______________________________________________________________________________

Robert Mackenzie: Joe, on Wednesday, you announced the “The First Law” graphic novel, to be published in a variety of forms. How did this come about? How did you put the team together, or rather, did the team come to you?

Joe Abercrombie: It was Rich Young, at Blind Ferret, who made the approach. I’d had a couple of much more traditional approaches before, but the combination of free digital, paid digital, and hard copy distribution really sold it to me. Rich then brought in Chuck to adapt, who he’d worked with on Wheel of Time, and suggested Andie as an artist. Soon as he sent the first character designs I knew he was the right guy for the job. Andie then suggested Pete for the colours. So my role, as with a lot of this project, was to say yes to things, with a tweak here or there.

RM: A big part of the announcement was about the extent of your collaboration. Chuck Dixon and Andie Tong certainly know their stuff, but how did it feel to let someone else bring their impressions to your world? Logen, for example, looks quite different to how I pictured him – were you involved with reshaping him, or are you letting Chuck and Andie have a relatively free hand going forward?

JA: I really wanted an artist who’d pick it up and run with it, provide their own vision of the material. I didn’t necessarily want what was in my head, I wanted to see how someone else interpreted it. And I was fascinated by what Andie came up with in terms of the designs. I think he’s got an amazing eye for costume and setting design – so the Union soldiers’ uniforms for instance have a sense of a 17th century European officer, but there’s also something decidedly alien about them, and you can tell that, say, the dresses of the Union women are of the same culture even though they look nothing alike. I gave a lot of pointers and references early on, and sometimes character designs came back perfect, sometimes surprising but fitting, sometimes needing changes of one kind or another. Likewise, with the scripts, Chuck has had a free hand. Clearly he’s got the text there as a reference and the adaptation is pretty comprehensive, so he hasn’t needed to do a huge amount of heavy cutting and reorganisation – generally he’s adapted pretty faithfully and what he’s brought to the project is his huge experience in pacing, in angle, in how to interpret all the things in the prose – thought, action, personality – through the visuals. Then I’ve tweaked the scripts a bit here and there afterward where there’s something important to a character, or to a later plot development, or just that I particularly liked or didn’t and needed to stay or go. I had total editorial control, in theory, but I tried to use that force wisely and for good. So it’s very much an ensemble creation, and one that I’m very happy with.

RM: Fantasy is a genre that has particular tropes which are familiar to the readers, and with which the First Law plays extensively – kindly and sage wizard mentors, noble barbarian warriors, lost princes, dark lords, and items of world shaking power – do you think your commentary on those tropes will translate across to readers who might not be as familiar with them?

JA: I’d like to think it works as a good story with strong characters, compelling action and a sense of humour whether you’re familiar with the genre or not, but are there really a lot of people out there who don’t know who Gandalf is? Or Merlin? Or King Arthur? I think a lot of these tropes are so fundamental not just in genre but in the bedrock of our culture that the vast majority of readers get where you’re going…

RM: The other thing which fantasy novels seem to have in abundance is violence. The genre often stylises it, but you treat it very seriously, part of which is being relatively confronting about it and its consequences. Through it’s early days, the first pages do seem less gory than their text counterparts. How have you and the team worked on translating the more graphic story elements to a visual medium?

JA: I always wanted to take a gritty approach to the violence, I guess you might say, to contrast with the simpler, more shiny and heroic approach I tended to see in a lot of the fantasy I read as a kid. I wanted the violence to feel visceral, involving, scary, unpredictable, to have consequences for victims and perpetrators both. Comics is obviously a different medium to prose, much more of the visual and less of the experience and emotion of the characters, so things will come across differently. I suppose the simple answer is that, as with the rest, Chuck has rendered my prose into panels, captions, and dialogue in the way he feels best gets the mood and the action across, I’ve tweaked that a little if I’ve felt I needed to, then Andie has drawn the panels in the way he felt fit with the style and approach, and again I might have made a change or two. Then Pete’s colours have been very important too. There’s a fair bit more violence coming up in the second issue. I don’t think there’ll be a lack of grit, though it is a different medium, a different feel.

RM: The depiction of women is a hot button topic in the comic book sphere. In fantasy comics in particular, there is a legacy of chainmail bikinis that we’re just moving past. You’ve gone on record before expressing some regret over how the female characters in your first trilogy ended up being portrayed, something that I think it’s fair to say you tried to course correct in your later books (I’m thinking of Monza and Shy South from your later books here). Is it something you’re looking at revising now you in some respects get a “do-over”? What sort of artistic choices can we expect to see made around the presentation of the story’s women?

JA: It’s a tough one. I think as a writer you should always be thinking about what you’ve done and what you could do better. But once a book’s out there it’s tough to change. We want to make this a faithful adaptation of the books so I doubt you’ll see any massive changes. I think it’ll be on a case by case basis, see what works, see if there’s anything I really feel I want to change when we come to the point of adapting it. I think I have written better and more central female characters in my later books, but I do still think there are some interesting women in the First Law, and hopefully Ardee’s sense of humour and Ferro’s thirst for vengeance will come across in the adaptation and give readers some vivid female characters to relate to.

RM: The motivations in your books are often pretty complex. You’ve said before that this is a conscious component of your work and that you’re trying to distance the world of fantasy from a moral black and white. Do you think this complexity will be as easy for readers to pick up on as in prose, particularly where your story is unfolding for some three pages a week over years?

JA: I think in moving from a prose to a graphic novel inevitably you lose a little nuance, lose some of the internal thoughts and feelings, lose some of the very intimate connection you can develop to a character when you’re right in their head with them. But with good art you can gain a lot in impact, in design, in spectacle, in expression. They’re different mediums with different strengths, but I hope at least some of the unique nature of the characters, their complexities and contradictions, will come across in the graphic novel version. I think they will.

RM: On that topic, some people have said that your books are pretty notably cynical about both the better angels of human nature and the societies which people build to try and regulate it – The First Law in particular. I think I recall you commenting that particularly in that first trilogy it was an attempt to invert the fantasy status quo. Is it all by design, or does that reflect how you really feel about the world day to day?

JA: I’m not necessarily a withering cynic with regard to real life, but I do feel the need for some cynicism, some sarcasm, some irony, some realism in the stories that I read. I guess I felt the need for something to sit on the other side of the scales from a lot of the morally simple, good vs evil, happy endings with the promised king marrying the promised princess and presiding over a golden age of prosperity for all type stories that I’d seen rather a lot of in the past. The First Law was really my attempt to look at some of the tropes and cliches common in fantasy and pick them apart a little, present more realistic, more cynical, more complex versions and see what happened.

RM: The Blade Itself (the book, not the comic) was published seven years ago, and was conceived and begun sometime before that. The fantasy landscape has changed pretty notably in that time in terms of reader expectations. The comics industry certainly went through a period of maturation where the subject matter became darker all at once, and it was noted that afterwards authors seemed to try to outdo each other regarding the “mature” trappings to the detriment of plot and character. Your works are very nuanced, but do you think that other writers struggle in the context of the prevailing trends? How do you feel about a perceived role as a harbinger or advocate for the increase in blood, assassins, anti-heroes and septic wounds in the fantasy market?

JA: Oh, I don’t know about that one – I’ve always just tried to write the sort of stories I want to read. It’s never been my intention to be part of a movement or advocate for anything but the best fiction that I personally was able to produce. Genres develop, change, shift to follow very successful examples, then swing back in other directions. I think there’ll always be a place for quality fiction written from a place of honesty, regardless of whether it’s cynical or optimistic, romantic or ruthless.

The First Law #1: The Blade Itself is out now from Blind Ferret Comics.