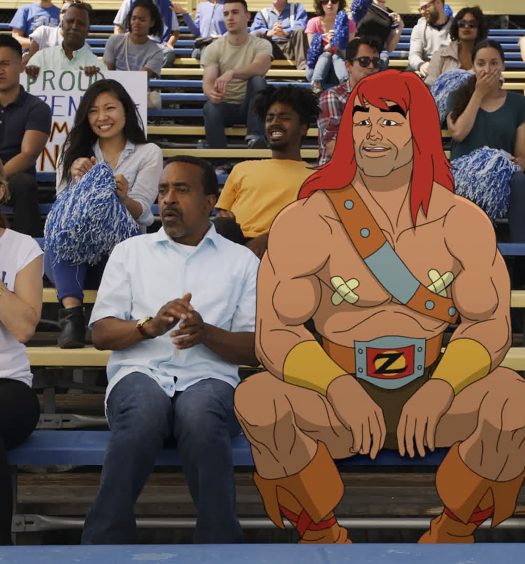

We sat down with Leo Birenberg, composer for Son of Zorn, to talk about his work, his life, and the movie Love, Actually.

Leo Birenberg is a voracious composer for film and TV. Right now he’s working on Fox’s live action/animated hybrid sitcom Son of Zorn, to which he contributes gloriously ludicrous Sword-and-Sorcery goodness from his own unique perspective. As a collaborator of Christophe Beck, he’s contributed additional music and production to movies from Frozen to Edge of Tomorrow to Ant-Man. We sat down with Leo to talk about his work on Zorn, where he came from, and what led to his career in composition.

Nerdspan: So, are you from LA originally?

Leo Birenberg: I was actually born in Kentucky, and I grew up in the Chicago suburbs, and then to went school in New York at NYU, and then came here six years ago. I’d consider it home at this point, since I’ve been here so long, but I’m not a native or a local.

NS: Okay, so you’ve talked before about being interested in music since you were tiny.

LB: I was the band geek extraordinaire growing up. My main instruments were saxophone, clarinet, and flute. I grew up playing in band and jazz band, singing in choir. I was really into musical theater since the time I was pretty little, so I was always singing. And it was always a hobby of mine to pick up new instruments and play them. I didn’t necessarily get good at them, but I would mess around on them and make music.

LB: I was the band geek extraordinaire growing up. My main instruments were saxophone, clarinet, and flute. I grew up playing in band and jazz band, singing in choir. I was really into musical theater since the time I was pretty little, so I was always singing. And it was always a hobby of mine to pick up new instruments and play them. I didn’t necessarily get good at them, but I would mess around on them and make music.

NS: So did you find, coming up on saxophone – maybe this was just my experience, but I felt like I got a really good ear for harmony.

LB: Absolutely! I’m not sure I’ve ever talked about this before, but I think playing saxophone is essential to the fact that I write music as opposed to becoming a good performer. In a concert band, when you play the saxophone, it almost feels like you’re a bit of an afterthought in some ways. So you end up playing all of these inner moving parts that you never hear, when your parents are listening in the audience. It gives you a great behind-the-scenes look at how music is constructed. And then, adding to that, if you play saxophone and you have a big jazz upbringing like I did, you just get thrown into the harmony whirlpool. Jazz is just all about harmony. So between those two factors, yeah. Absolutely, I do.

NS: I don’t know if I’ve ever talked to anyone else who writes who’s described that experience that same way. I feel so validated right now. So you came into Son of Zorn because they came across your website, you said? They got in touch with you there?

LB: Yeah, so what happened was I got an email from one of the executive producers on the show, Eric Appel, who’d watched a previous show I had done called Big Time in Hollywood, FL, which was on Comedy Central for one season and I don’t think anybody watched it. But it was great, if you ever have three and a half hours and just want to binge it. And he loved the show, and what I’d done for that show, and he was just gearing up to direct the pilot for Son of Zorn, so he reached out and said, “Hey, dude, want to come by and talk about this show that I’m about to direct a pilot for?” So I swung by Fox for a meeting, and we just all clicked immediately. Then, I did the pilot, and then the show got picked up, and here I am. It goes to show two things. One: keep your website updated, and Two: It’s fun to work with people you get along with.

NS: So I was going to ask about that. It seems like there are a bunch of different things happening with the Zorn music. Because you’ve got the Zephyrian stuff, which is very Conan. There’s the “family sitcom stuff,” but then even that seems to be broken down. There’s a sort of ironic detachment when Zorn is forced to do mundane things, but then the music also seems capable of turning on a dime and hitting on earnest emotion when it needs to.

LB: Yeah. We wanted to get the whole spectrum in there. I think the very very first thing I wrote was the title card, which comes from the Zephyrian thing. It’s just a six-second bumper that goes “ba-bum, ba-bum, ba-buuum!” Very much in the He-Man, ‘80s/late ‘70s, animated style of work. And then from there, we wanted to do a family sitcom sound, except try to make what the fabric is woven out of still be from the Zephyrian world. So that family sitcom music all usually has some sort of ethnic drum accompaniment, or is played on weird, not-quite-identifiable, guitar-like string instruments, or flutes. I’m really into flutes, since I grew up playing saxophone. So we try to write that ironic family music – something not dissimilar to what you would hear in Family Guy, although I would say even, go back to a more 1970s family sitcom.

NS: Yeah, because Family Guy has all that Old Hollywood big band stuff woven in.

LB: Right, but what we were doing was trying to fill that same roll that music in Family Guy is filling, but with our quasi-barbarian palette. It’s just jazzy enough in that really old-school Leroy Anderson light-classical way. So it’s a very fun style to come up with quirky little ideas. And all of us who work on the show feel that what keeps it engaging and what makes it fun to work on is actually when it’s most emotional. And treating Zorn like a human, that’s the entire crux of the show. Like, sure, he’s weird. Sure, he’s from a foreign country, but he’s a human too, and he has all the same emotions and desires, even if he arrives at them through a slightly different way. It was really important to us to be able to appeal to that pathos. We worked hard to come up with some emotional settings for the themes and use them whenever we can.

NS: I feel like it really works.

LB: Well, thank you!

NS: Thank you! I went back and watched a couple of episodes, but I also got distracted because the stuff on your website was so damn good. But there was a moment in the pilot where Craig and Edie sit down and they’re talking, and I was struck by the abrupt sincerity of it all.

LB: Yeah, I mean we did that all on purpose. I think it makes the comedic highs higher, when you ground it in a realistic emotional base.

NS: So when you go through and you’re deciding, musically, when to go down the rabbit hole with Zorn and when to stay in that more grounded world, is that all gut? Is that something you decide in conjunction with the director?

LB: It’s a bit of both. The general working process on this show is a little different than other TV, because it’s like making two shows in one, with the animated aspect and the live action aspect. So they shot the entire season at the beginning of this year, and episode by episode we have multiple teams of animators working at Titmouse, the animation studio. So there’s a constant turnover that happens a few months later, after it’s been cut together, where the animation comes in. So I take a first pass at things once there’s an animatic lock, which is a locked cut that has stick figures drawn in it of Zorn. Most of the dialogue is in there, already recorded, although a lot of the time it changes later. But it’s a fairly tight assembly that the animators work from to come up with the animation, and then I do an early pass of the music. I’ll sit down with Eric, and we’ll kick around ideas. We like to repeat themes from previous episodes, especially within the family unit, because we want to keep it consistent. The show is so short, it’s only 22-minute episodes, so we want to make sure there’s a certain familiarity in the music, a lot of times. We make a framework of “Oh, okay, let’s use this here…let’s start with that idea over here and change it,” and that always leaves a couple of, as you described, some of the “down the rabbit hole” moments. “What are we gonna do here? It’s larger than life, something crazy is going on.” And a lot of times I just go with my gut and so something ridiculous. There’s a scene in an early episode where Zorn gets in a war with the guy in the office next door over a bottle of hot sauce. Did you watch that one by any chance?

NS: Oh my gosh, no!

LB: I think it’s the third episode. It’s a really funny one; I would suggest checking it out. But there is a lot of war music that happens, and all in Zorn’s head. It’s a combination of over-the-top action music and me doing crazy tribal screaming that I just came up with. And it’s all me, but you’d never suspect. It was one of those where I just said, “Hey, check this out! I did something insane,” and then we went with that. There’s another episode that I’m really fond of, it’s the Thanksgiving episode, where Edie’s mother-in-law comes to visit for Thanksgiving. She hates Zorn, but he shows up anyway. And in some confusion he accidentally kills her by feeding her a poisoned pie. So long story short, Zorn calls his doctor in Zephyria and figures out that he needs to make a magic potion to bring her back to life. So there’s this climactic scene where they’re all in the bedroom, trying to bring her back to life, and Edie doesn’t know about it yet. It was one of those things where I saw it, and there was no music in it, and I said, “this would be so funny with just some dramatic, Mozart Requiem-esque, quasi-operatic liturgical thing,” so I wrote a new setting for a requiem mass, and sang the ridiculous high tenor part all by myself. I didn’t even discuss that with anyone; I just do these crazy ideas and send them in, and usually people like them.

NS: That’s awesome! It sounds like you have a lot of leeway musically, and you also maybe have a little more time than TV composers usually get in terms of the way the show’s laid out.

LB: In terms of initial creative process, I do have more time to think up some ideas. By the time we do get on a more natural schedule as the animation comes in, we do a final spot where the sound people come in too, and we all watch it, and the mix is like ten days later. But I do have a little more time and luxury at the front half of each episode. I do get a lot of creative leeway from the producers, which is awesome. It’s so fun. I think anyone on the show will tell you that there’s a fair amount of leeway in my department, and I know the animation guys are always coming up with cool stuff and ideas. It’s a very open, discussable environment, and everyone who works on the show loves the concept. So we all bring our A-game in terms of day-to-day, random creativity for moments like that.

NS: It sounds like you do a lot of the playing yourself. I’m wondering what the breakdown is between you messing around on exotic flutes and string instruments versus session musicians versus sampled stuff.

LB: Almost everything is samples if you’re hearing orchestra or percussion. Most of that is samples. Piano. Then anything that sounds kind of wacky and flutey or occasionally a drum, it’s probably me. A lot of time vocals are me. I recorded a little bit of guitar with a session musician, just smattering here and there throughout episodes if there’s a very featured guitar part that needs some cool instrument that I don’t have that I need to see someone else play before I know if I want it or not. Anything that samples can’t do. We haven’t really done a recording date, officially, with an orchestra on this show yet. But we did, for the Christmas episode, record a choir. An adult choir and a children’s choir. And this again was one of those crazy out-of-left field ideas that I had when I saw the initial cut. “What if we did this entire episode with Christmas music, but it’s not about Christmas. It’s all about Zorn’s version of Christmas, this revenge holiday called Grafelnik.” So we actually hired a children’s choir and an adult choir, and we shacked up in a studio all day and recorded all these original carols that I wrote. And I also took the opportunity to add choir to all the other cues, so it’s super big and operatic. So that’s the biggest session we’ve done. It was super fun, and hopefully we get to do more things like that.

NS: So that was maybe your Christmas present, was getting the choir.

LB: That was my Christmas present from Fox, absolutely.

NS: I skipped ahead to watch that one, because I saw the sessions for it and thought, “Okay, it looks like they’re having fun doing this.” And it’s great, especially in the little moments where the music will maybe be buried under dialogue for a second, and then you hear the choir rise up, and they’re singing about vengeance amidst all the sleigh bells. It’s great!

LB: Yeah, it was really fun. I really went all in on that episode. The entire process, from talking about what we were going to do to holing myself up and doing it…that one was crazy because they gave me so much leeway. As composers in 2016, we mock up everything. Nothing is up to chance. By the time we get to the final mix, the producers have heard every single music cue and it pretty much sounds identically to what it is. And that goes for huge Hollywood movies to Son of Zorn. On this episode – because there were all these lyrics involved, and this choir arranging was such a specific thing, especially this carol-y thing, there’s not really – short of hiring singers to demo it, there’s no way to make a digital mock-up that’s convincing. So I kinda just played all the pieces for them on piano and was like, “You guys gotta trust me here. If you’re not cool with that, let me know, and we’ll figure something out,” and they were like, “No. Do it. I’m sure it’ll be great.” So I just disappeared and did it, and we recorded it, and the entire process was so fun.

NS: That’s awesome. So another thing – very little to do with anything, but in that video you mentioned watching Love, Actually.

LB: That’s my favorite movie.

NS: Okay, I feel like it’s really underrated! To be as popular as it is.

LB: I feel like people write it off as a silly, meaningless holiday thing. But the acting is awesome. Despite the fact that it’s pretty ridiculous, the script is pretty tight. I think Love, Actually being a good movie has been diluted by the fact that now we have really bad versions of it.

NS: Yes!

LB: I feel like the ever-increasing pool of multiple-storyline things has diluted how good Love, Actually actually is.

NS: It almost plays as though Quentin Tarantino directed a romantic comedy.

LB: Please elaborate.

NS: Two things – first off, the way you’re jumping from story to story and the way that they weave together, it reminds me of Pulp Fiction in that regard, maybe writ large. But I also feel like Tarantino is kind of a remix artist as much as he is a director.

LB: That is definitely true. I would agree with that. I think that movie is tightly constructed, as tightly constructed as that kind of movie can be.

NS: Yeah, and it’s like, “We’re going to work through every romantic comedy plot, every trope, we’re going to address them in turn, do the best version of them,” and maybe it’s not a fair comparison, but I always feel like I’m watching…if Tarantino adapted Nora Ephron instead of Elmore Leonard.

LB: Right! That…that was a well put-together metaphor.

NS: It’s just a fun movie! Okay, so you’ve been working with Christophe Beck for a long time.

LB: Yeah. When I moved to LA, I did this grad program at USC. There’s not many places you can go and study film music, but this is one of them. It’s one of those programs that’s very much about building industry connections, since it is Hollywood, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re writing music or doing whatever. Hollywood is Hollywood. You need to know people, and go out and meet people. So the program had a heavy emphasis on that. And while I was there, I started working for this orchestrator/conductor/composer named Tim Davies, who, actually, I had met my freshman year of high school. He was a featured composer who came, and we played a bunch of his music at our spring jazz concert. He is a phenomenal big band writer. And basically through some really well-timed needs of help and availability, I ended up interning for Tim, who conducts all of Chris’s scores. And after a few months of that, Chris needed some help, because his long-time assistant was going to get married, and they needed some extra help around there. So Tim introduced me, Chris poached me (as Tim likes to say), and then I was a Hollywood assistant for a composer. I did a bunch of grunt work and made coffee and ran errands, and after a little bit of that…Chris basically trained me. I knew how to write music, but writing music for a movie is so much different from a logistics point of view and a technological point of view, and an “application of musical ability” point of view. First it was revising things, then it was writing some really short easy cues, and then it was writing some not short easy cues, and suddenly you’re writing a ton of music. Chris is a dream mentor in that he let me be incredibly hands-on with everything, and didn’t micromanage at all, just dumped a bunch of responsibility on my plate. I got exposed to everything from Disney music on Frozen to dark, dark gritty sci-fi on Edge of Tomorrow to superhero music on Ant-Man to heist music on Tower Heist, and you file all that away in your head and you can just draw on it whenever you need to. I think anyone who works in any department of film will say this, and I’m sure any composer will say this…even though every movie is different, every project is different, you find certain parallels in problem solving. And once you’ve solved that many musical, dramatic problems working on that many movies of different kinds, then when you approach the next one, the answers reveal themselves much more clearly about how you should play a scene, and how you should deal with the fact that it’s a little bit shorter than your theme, so what can you do to make something good? That was amazing. I couldn’t have asked or hoped for anything better in terms of an introduction into the industry.

LB: Yeah. When I moved to LA, I did this grad program at USC. There’s not many places you can go and study film music, but this is one of them. It’s one of those programs that’s very much about building industry connections, since it is Hollywood, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re writing music or doing whatever. Hollywood is Hollywood. You need to know people, and go out and meet people. So the program had a heavy emphasis on that. And while I was there, I started working for this orchestrator/conductor/composer named Tim Davies, who, actually, I had met my freshman year of high school. He was a featured composer who came, and we played a bunch of his music at our spring jazz concert. He is a phenomenal big band writer. And basically through some really well-timed needs of help and availability, I ended up interning for Tim, who conducts all of Chris’s scores. And after a few months of that, Chris needed some help, because his long-time assistant was going to get married, and they needed some extra help around there. So Tim introduced me, Chris poached me (as Tim likes to say), and then I was a Hollywood assistant for a composer. I did a bunch of grunt work and made coffee and ran errands, and after a little bit of that…Chris basically trained me. I knew how to write music, but writing music for a movie is so much different from a logistics point of view and a technological point of view, and an “application of musical ability” point of view. First it was revising things, then it was writing some really short easy cues, and then it was writing some not short easy cues, and suddenly you’re writing a ton of music. Chris is a dream mentor in that he let me be incredibly hands-on with everything, and didn’t micromanage at all, just dumped a bunch of responsibility on my plate. I got exposed to everything from Disney music on Frozen to dark, dark gritty sci-fi on Edge of Tomorrow to superhero music on Ant-Man to heist music on Tower Heist, and you file all that away in your head and you can just draw on it whenever you need to. I think anyone who works in any department of film will say this, and I’m sure any composer will say this…even though every movie is different, every project is different, you find certain parallels in problem solving. And once you’ve solved that many musical, dramatic problems working on that many movies of different kinds, then when you approach the next one, the answers reveal themselves much more clearly about how you should play a scene, and how you should deal with the fact that it’s a little bit shorter than your theme, so what can you do to make something good? That was amazing. I couldn’t have asked or hoped for anything better in terms of an introduction into the industry.

NS: And I feel like Zorn is a microcosm of that in a lot of ways. You described having to become a stylistic chameleon, and I feel like there’s a lot of that within the world of Zorn itself.

LB: Oh, absolutely! I might even say that that’s, at least right now, what I’m best at, or being a stylistic comedian. In Zorn we do it all the time. In the show I did before Zorn, Big Time in Hollywood, FL, we hit every genre ever, which I think was part of the reason Eric was drawn to that when putting Zorn together. That’s fun. It’s fun to mix it up. I get bored if I’m writing the same style over and over. I have my favorites, but it’s fun to mix things up and do a little bit of everything.

NS: So what are your favorites? What music led you to composition?

LB: Ooh, that’s interesting. Because I actually think the music that led me to composition is different than the music that’s my favorite.

NS: Well, that’s fair! So give us both.

LB: So I think what led me to composition is…I had a big background in jazz growing up. And I just love Pat Metheny, the guitar player. What I love about him is the pieces he writes are these long-form, very developmental works of art. It’s like a symphony. They’re not always that long. Or like a tone poem, just presented for a much more adventurous set-up jazz combo than your typical jazz album. And I just loved that stuff. I loved listening to it; I loved transcribing it. There’s a bunch of modern big band music that is similar, I think. So that long-form jazz really got me into liking the building blocks of music and becoming more interested in them. Then, I showed up to college – I did my undergrad at NYU – and at this point I said, “Okay. I want to study music composition.” That’s what I’d been accepted for. But then, despite the fact that I sang in chorus, and played saxophone and clarinet and flute, I didn’t really know anything about classical music, so I just wanted to show up and learn about Mozart. So I just holed myself up for all of undergrad and studied classical music and opera. I’m a huge fan of Wagner. It’s probably my favorite. I think he was writing film music before there were movies, so there was a natural connection there.

NS: Well he had that whole concept of the leitmotif. [Giving each character a theme and then using that theme to signify the character – you see a lot of it in film, especially in Star Wars.]

LB: Yeah, I mean he’s got…he’s got all the best words, man. Leitmotif. Gesamtkunstwerk, which means “total artwork,” which was his concept for…he wanted to transcend opera and create something that draws on all the realms of the arts. Visual, sonic, and weave them together into one thing, which is how he viewed his final few operas. I feel like he just didn’t live long enough to figure out that that’s what a movie is, basically. I think he would’ve been a genius filmmaker and film scorer. He’s got one other one that’s just unpronounceable German. Ersichtlich gewordene Thaten der Musik? I’m sure I butchered the pronunciation. But it means “deeds of music made visible.” And I think that is just a beautiful way of talking about film music and music in general. Anyway, I made this big transition into classical music and opera, and through this whole thing I wanted to do film music. I think a lot of people who are into music right now want to do music for film and TV. And now I think a lot of my favorites are, I love writing for big orchestra; I love writing for colorful orchestra; I love writing Disney music, or Disney-esque music. I think partially because growing up a woodwind player, there’s a lot more room in those projects to fill them up with different, colorful woodwind flurries, which are always fun to write. That’s the stuff that you grow up with! Watching Disney movies. I feel like when you’re a kid, the music in the background of whatever you’re watching is so important, and so it’s fun to appeal to that younger version of yourself.

NS: Well, and you think about it too, nowadays…I don’t want to assume everyone’s experience, but most homes don’t have Wagner playing in the background. But they’ll have Disney, or they’ll have Star Wars.

LB: Star Wars is what I was about to say. Absolutely.

NS: That was when I fell in love with all that stuff.

LB: Oh, me too! When I was like five years old, I just wanted to direct movies. For years, I used to just make movies on an old mini-DV camcorder with my friends and we’d edit them in iMovie version 1. And we’d cut in the Star Wars music in pretty much all of them. Because when I was four years old, I distinctly remember watching Star Wars. And that’s been a huge part of my life.

NS: That just makes me happy.

LB: Good! It should!

NS: I think as far as actual questions go, that’s about everything, but I always like to ask: What’s a question, as you’re doing press, as you’re doing interviews – what’s a question that you wish people would ask you, but no-one ever does?

LB: Oh, man! I don’t even know! I think honestly you hit it more clearly by asking…okay, I’m not sure what the question would be, but the answer is definitely what I said about liking long form jazz. And that’s how I got into writing music versus what I write day-to-day now. What do people not ask me? I don’t know; I always like when people just ask me random stuff about myself that has nothing to do with the show or anything, which no-one ever does. So if you have any random questions.

NS: Well I started to ask how long you’ve had [your dog] Napoleon, but I decided that was too off-topic.

LB: I can talk about this dog all day. He is completely passed out. We were in Big Bear over the weekend and he was playing with some other dogs, so he’s slept the last 16 hours. I got him when he was 7 weeks old and I was living in New York, doing my final semester at NYU. I didn’t know I’d be moving across the country to LA at that point, so I might not have gotten a dog if I’d known that. But now he’s about to turn 7, on January 3rd, and he is incredibly lazy. That’s his defining feature.

LB: I can talk about this dog all day. He is completely passed out. We were in Big Bear over the weekend and he was playing with some other dogs, so he’s slept the last 16 hours. I got him when he was 7 weeks old and I was living in New York, doing my final semester at NYU. I didn’t know I’d be moving across the country to LA at that point, so I might not have gotten a dog if I’d known that. But now he’s about to turn 7, on January 3rd, and he is incredibly lazy. That’s his defining feature.

NS: That’s nice. We adopted a puppy from a couple who had to move, Yoshi, and she is a completely overwhelming ball of energy and neuroses, so a lazy dog sounds nice.

LB: It is very nice. Sometimes I’m just like, “dude, don’t you want to…do something?” But day to day it’s pretty nice, because I work a lot, and he’s happy to just sleep in the couch in the studio all day. I feel like I’m not going to be that lucky when and if I have kids.

NS: You have said so many things today that are hitting me where I live, man. Thank you so much. Do you have any last words for us?

LB: My last words are “Watch Son of Zorn. Sundays after The Simpsons. 8:30 Eastern and Pacific time.”