Emperor’s New Clothes is Crowdfunding Laid Bare

Kickstarter, the sovereign of the people’s crowdfunding revolution, has risen far from humble beginnings. For 22 consecutive days in 2006, its most-funded project was New York Makes a Book, which raised only $3,329 over the life of its campaign, a hair over its $3,000 goal. Progress was swift, however, as chatter about the site took hold. In just over three weeks, another project assumed the most-funded throne, earning $7,711 (four times its goal). It only took 31 more days for a Kickstarter project to breach $15k, and the bar has been climbing ever higher. The current most-funded project, the Pebble smartwatch, raised more than $10 million in a little over a month. That’s 68,929 people who thought an app-centric customizable watch face was a good idea.

Although Kickstarter has grown rich and corpulent as its empire of copycats–the Fundlys, the GoFundMes, and the Indiegogos–has spread, it’s never lost sight of its dream. Sure, there have been a few words added to the FAQ about “accountability,” but that’s just the platform judiciously covering its rear against a maelstrom of increasingly lucrative transactions. The actual status of those transactions is something on which Kickstarter’s remained firm since the beginning: it isn’t simply another e-shop. “Backing a project is more than just giving someone money, it’s supporting their dream to create something that they want to see exist in the world,” boasts the website’s FAQ. Every Kickstarter project, from the smallest indie art show to the biggest tech innovation, started out as somebody’s pipe dream, and there’s always a chance that’s how it will end up.

It hasn’t happened yet, at least not in a major way, but the possibility is always there. That’s the secret fear of all Kickstarter backers: that a project in which they’ve invested heavily, whether financially or emotionally, will fail to deliver. In fact, the crowdfunding public (and the mass media) seems to be so hung up on the chance that the next big super-funded project will turn out to be nothing but hot air, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we’re all secretly hoping somebody will pull the wool over our eyes. There are many Kickstarter projects that seem too good to be true, and that’s mostly because they are–but we spend money on them anyway. As long as we’re not the only ones being fooled, it’s no different from being one of the hundreds of thousands of people who “bought into” Betamax, the Sega Saturn, or the Jaguar CD.

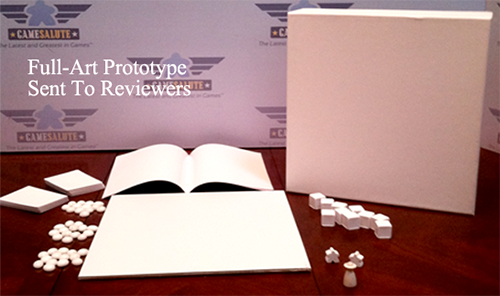

While there’s no shortage of Kickstarter projects making promises they’ll never be able to deliver, Emperor’s New Clothes, a tabletop gaming project by GeekDad Jonathan H. Liu, takes the opposite approach: it makes no promises whatsoever, asking its backers to share in the creator’s dream, to use their imagination in deciding whether this project might be worth their hard-earned coin. Its prototype images are blank, its artists are incompatible, and even the rulebook and print-and-play components, provided free of charge so that potential backers “can see exactly what they’re getting for their money,” are nothing but white space. It’s up to you to decide what they might be. In practice, this isn’t much different than any other Kickstarter campaign, in which the attention-grabbing videos and mock-ups are as far from the finished product as original series Star Trek is from the J.J. Abrams films. Except here, there are no empty promises; or rather, the promises are so obviously empty, the lies so blatant, that it’s become the most refreshingly honest campaign on Kickstarter. Think of it as the meta-Kickstarter–crowdception, if you must.

The product described on the campaign’s main page is part gamer’s game, part Baron Munchausen. Based on the story by Hans Christian Andersen, it puts players into the role of the tricky swindlers, the vain Emperor, the gullible townspeople, and the sharp-eyed child from the tale–all at the same time. There’s lots of talk about role selection, scoring tracks, and resource gathering, but it’s difficult to see exactly how it will play out in action. That’s because of the ROOS: Regulated Operator Optical Screenprinting, a state-of-the-art printing technology pioneered by Wysiayg Press. Discovered accidentally when attempting to engineer for a pigment that makes colors more easily distinguishable for the colorblind, ROOS takes the challenge a step further, putting blind, colorblind, myopic, and normally sighted people all on the same footing. A trick in the printing process guarantees that the cards, cubes, and other components included in the game appear completely blank–except, of course, to a small but elite subsection of the population. Could you be one of them? Cough up some cash, and you might find out.

Hoke’s Games, the design studio behind Emperor’s New Clothes, is an unknown commodity in the game design world, and their slogan, “the name you can trust*”, doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence. However, the publisher, Game Salute (Empires of the Void, Alien Frontiers, Zpocalypse) is a Kickstarter veteran. Emperor’s New Clothes has their Springboard Seal of Quality, meaning that backers are likely to get something…what that is, or might be, is still up for debate.

The full impact of the ROOS process is doubtless something that has to be seen to be believed, but even without “revealing” any of the game’s details, Mr. Liu has already well exceeded his $5,000 goal, proving that there’s more than one person willing to get behind a dream for the pure joy of riding it out and seeing what happens. This is Kickstarter in its purest form. Its backers, particularly the earliest ones, are literally throwing their money at a dream project they can only imagine. Is there more here than meets the eye? Is this anticipation a part of the game itself–the game of knowing you’re being duped and hoping that you’re not? Is this the beginning stages of an alternate reality game, or is it some sort of elaborate litmus test, as Mr. Liu seems to suggest with the following words:

“That’s the reason for the ROOS: wouldn’t it be great if I could simply not see any of the Kickstarter projects that won’t actually satisfy me? Can you imagine how much easier it would be to sort through your inbox if half (or three quarters) of the messages simply looked blank, because they didn’t actually apply to you? … So I’m giving it a shot: by making it easier for some folks to write off my project as uninteresting, unfunny, meaningless, I hope to find those people who will see Emperor’s New Clothes as interesting, funny, and full of meaning.”

I’m one of those people. Whatever souvenirs I end up with, this is the authentic Kickstarter experience, the dream I bought into when I made my first pledge on the site. This is crowdfunding laid bare.

March 13, 2013

Great article. With all the Kickstarter campaigns going on lately, it’s helpful to learn more of the history behind all this stuff.

P.S. I love your author photo!