Daredevil – A Look Back at the Man Without Fear, Part 2

(Editor’s Note: The following article was originally published on September 10th, 2013. Part 1 can be found by following this link. The author’s coverage of the recent Daredevil trailer can be found here)

So, last week, I used the casting of Ben Affleck as Batman as a flimsy excuse to catapult into my favorite comic of all time – Daredevil. Daredevil’s been a lot of things over the years, but even though the book’s seen its creative ups and downs, it’s always been just a little different from anything else out there. I’m looking at a different creator every week to show just what exactly sets Daredevil apart.

If you’re talking about Daredevil, you have to talk about Frank Miller first.

Frank Miller is a well-respected figure in the industry. Between Sin City, 300, Batman: Year One, and Dark Knight Returns, he’s more than secured his place in the canon. But I’m always surprised at the number of people who don’t know that he cut his teeth on Daredevil. It’s a shame, too. Not only is it a defining arc for the character, it’s also some of Miller’s most subdued, most human storytelling. This is “Year One” Miller, not “All-Star Batman” Miller, and it’s phenomenal.

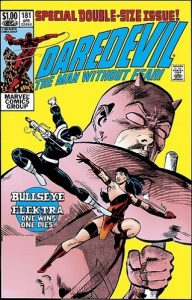

Miller started out as a penciller. Daredevil, at the time, was written by Roger Mackenzie, and the upstart Miller’s pencils were inked and tidied by Klaus Janson. But Miller began to chip in more and more story advice, and when Mackenzie left, moved in to writing and drawing the book himself. The accepted “Miller run” is 158-191, but that’s a little deceptive – the book starts out pretty stock superhero stuff, and gradually evolves as the fledgling artist asserts himself.

Miller brought a lot of things to bear on DD that either hadn’t been seen before, or hadn’t been seen in ages. He was a huge fan of Will Eisner’s The Spirit, and it shows in his panel layouts. Each page has an architecture that contributes to the mood of the scene. For a business meeting in The Kingpin’s office, the Fisk Tower dominates the left side of the page while the meeting plays out in squeezed panels on the right. Fisk’s dominance of New York and the meeting is solidified through the prominence of his tower, and the claustrophobic panels accentuate the tense atmosphere within. Miller takes the size, shape, and frequency of his layouts, and uses them to “pace” the story the way you would a film. He realized the unique possibilities of the art form, even while borrowing from another. It’s the old Marshall McLuhan adage – the medium is the message. Miller’s a master at drawing the eye where he wants it, when he wants it. If the art doesn’t look all that shocking today, it’s only because so many people have built on the groundwork that he laid.

A lot of words get thrown around to describe this run – “dark,” “gritty,” “realistic,” – so much so that Alan Moore wrote a satirical short called “Dourdevil,” lampooning Miller for being so grim. Having Alan Moore make fun of your comic’s self-seriousness is like having Keith Richards tell you to lay off drugs. Still, Miller did a lot for subject matter in comics, as well. There is of course the obligatory-for-the-era “drug story,” but this one – set in a school where a trusted coach is dealing – makes the risk intimate, immediate, and present. Drug use isn’t just the purview of cartoonish “punk” thugs – it’s something that permeates society.

Of course, it’s also important to look at what Miller did for the Daredevil mythos – for a book that gets the word “gritty” thrown at it so often, there sure are a lot of ancient, immortal ninjas hopping around. This run is where we start to really dig into Matt Murdock’s backstory – the way his heightened senses overwhelmed him, the way that a blind ninja master known as “Stick” came into his life and helped him sort the signal from the noise – we see his college years, we see his struggle with his home life, we see him cross paths with the mother who walked out on him. For a book that had been running for so long, there was a lot left unsaid about what brought Matt to becoming Daredevil beyond the boilerplate origin-story one-pager.

Miller also employed some characterization techniques that would become favorite in subsequent years. Before Alan Moore started deconstructing superheroics in Watchmen, Miller started playing around with what these characters would be like in the “real world.” The villains, in particular, became much more interesting. Stilt-Man is rendered as a buffoon with a Napoleon complex, an also-ran who serves primarily as comic relief. Gladiator struggles with civilian life, with the help of a social worker. Bullseye suffers a brain tumor that serves to explain his past behavior while making him more unpredictable.

Later writers have built on this. (I’ll talk about it more in particular when I talk about Bendis.) People have tried to “ground” their comics stories before and after, but Miller’s Daredevil represents a huge leap. For a writer known for larger-than-life caricatures, this is some of the most human storytelling comics ever saw.

* Miller actually returned to Daredevil a few times – most notably with John Romita, Jr. for the miniseries Man Without Fear, which shares a similar place as Batman: Year One and Dark Knight Returns – “We’re not gonna call it canon, but everyone draws from it anyway, because it’s awesome.” You can tell it’s later-period Miller because it has more prostitutes, but it’s still some of the best insight into Matt’s character ever written. He also produced Born Again, which condenses the basic arc of his entire first run into 8 issues and cranks it up to 11. It’s fantastic, but it’s not a great starting point, since it assumes you already have the basics. Start with the first run. It’s long, but it’s long because they kept him on