Comics Review: Lazarus #3

“Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

In a month that can be legitimately described as harrowing for both your correspondents, nothing serves to strengthen the resolve and lighten the heart than the contemplation of art. If you’re with us now, we presume you’ve come past the first two installments of Lazarus Rising, have liked what you’ve seen, and are with us for the long haul.

Bearing this in mind, we’ve got a very light preamble this week – you know what Lazarus is, and you know why we like it so much. As per usual, this is commentary heavy and spoiler rich – we’re assuming you’ve read the issue by now (and an advantage of taking a week to digest and write-up means we’re usually right). If not, turn ye back, pick up Lazarus #3 and then join us again.

Enough prologue! On with the good stuff:

Lazarus #3

Through the first two issues, the Lazarus team have painted their story through layering small pictures of a wider world, using profiles of individuals and places to slowly inculcate in the readership a sensitivity to their striking world by presenting subtle, compelling and often frustratingly ambiguous moments from the lives of the Carlyle clan.

With the third issue, the narrative has changed gears. With Eve out in the wider world, and the Morrays and their servants reacting, new contexts and comparisons arise that providing certainty and momentum in preparation for closing out the first arc without abandoning the excellent “Show, don’t tell” principles that have carried Lazarus so far. A series of clever contrasts and comparisons have crystallised a sharper understanding of the Carlyle family, resolving many of the hints or ambiguities at the heart of the story to date. This week, we’ll look over a number of those complimentary and contrasting pairs and dig into our sense of where they take the story.

The Two Faces of Eve (We had to do it eventually)

From the very cover of the issue (in which we see Eve shown through a reflection of herself in blood – conjuring up both images of violence and family), Eve herself is a marked study in dualities, a contrasting pair of attitudes that nevertheless form a cohesive whole.

For all Eve’s previously depicted qualms and sensitivity, this issue puts at the forefront that she is herself both the product, and enforcer, of an incredibly unfair neo-feudal system. Now outside the ‘safety’ of the Carlyle territory, we have seen her demonstrate a level of steely confidence in the face of danger and pride in her position very different to the deference and insecurity she displays around her own family.

We saw some of this in her investigation at Harvest One, but previously, when not on the back foot with her relations, we have seen her competence displayed through primal atavistic rage or cautious and empathetic compassion. Here, she is dispassionate, almost arch, in her recourse to violence. Using speech bubbles as a pacing device for fast-moving violence is a classic trick, difficult to pull off, and is brilliantly utilised on to show just how inhumanely deadly a Lazarus is from the perspective of the unenhanced. Such display also emphasises how alien Eve’s cultural willingness to resort to violence is (and should be) for modern sensibilities. The world of Lazarus may only be a single step in the future, but as we discuss below, it is a hell of a steep step.

In this issue, the dismemberment of the Morray Sergeant marks the first time we have seen Eve employ considered violence unreservedly, and indeed, casually. Compared to her previously articulated perspectives on violence, her flip flirtations about refreshments with Joacquim after she maims and he executes the man (ah, the return of the food-on-a-platter motif again!) are very notable. This isn’t, we believe, a question of her acting out of character, but it is instead a stark reminder of the less palatable aspects of Eve’s character – of how Eve has a specific purpose and how, when called upon to fulfill that purpose, she is willing and capable of fulfilling that purpose. We concern ourselves below with neo-feudal societies, as the world of Lazarus is, but of paramount importance in their assessment is that they often take on characteristics of an “honour” culture – expressed in contemporary terms as a culture concerned with the maintenance and loss of “face”.

Everything we know about Eve so far indicates that, more than the others we have met, she sees the Waste as people. This issue hammers home that, when her doubts or moral qualms rub against her sense of ‘face’ or honour, face comes distinctly first. Indeed, post-maiming, she gives every indication of supreme satisfaction, not only feeling she has served her family well, but also of performing well in the social exchange on a personal level – something very important given the burgeoning young love that the issue portrays.

Importantly, Greg has contrasted this ‘cyberpunk samurai’ display of face-saving in front of the ‘enemy’ Morray with her reversion to a flirtatious teenage girl in front of the ‘peer’ Morray. Only 19, we are finally given a chance to see her looking her age, seeming younger and more emotionally vulnerable through this issue than she has in the past, and especially so in the porch scene. While this elegantly serves the changing mood in that scene, we also have to note the Doylist truth that Michael wasn’t entirely aware of Eve’s age when he first drew her. Indeed, we get the impression of a sly in-joke on page 9 with the reference to Joacquim thinking Eve was older than she was, five years ago. This contrast between vulnerability and social positioning is another study in dualities – that assuming a role, even a potentially objectionable role, gives people (particularly teenagers) a strength they feel that they lack on their character alone.

A particular piece of structural finesse can be found in the first three issues of Lazarus. They have followed the archetypal pattern of coming-of-age stories about finding your place in the world. The facts of the world haven’t been twisted to reflect this idea – this is not Eve’s first time out in the world, and she wasn’t literally born yesterday – but the symbolism of the work remains clear. In Issue #1, Eve (dies and) experiences a violent “rebirth” – she literally comes into a state of existence from non-existence, a state of life out of death. This may be a death that lasted only a few minutes, but in a very real sense we, as the readers, witnessed a few scant days ago the beginning of her life. Issue #2 then reflects the tribulations and impulses of childhood: difficulty in interacting with siblings, testing the boundaries of your home and supervisors, seeking the approval of your parents. Issue #3 moves Eve squarely into the realm of adolescence – she is out in the world independently, and as we discuss below, experiences the pangs of teenage love for a long-held crush. As soon as we saw Joacquim at the end of Issue #2, we suspected this moment was coming, because it forms part of the pattern subtly underlaid in all of Eve’s life as we have seen it to date.

Lazarus & Lazarus

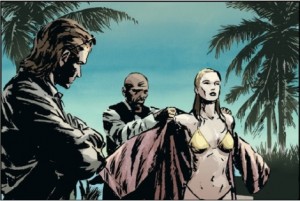

This duality we have seen within Eve is mirrored by a similar dichotomy in Joacquim and with Joacquim (as between he and Eve). Physically, Joacquim is as far from ‘type’ as Eve – his lithe, whipcord physique and ponytail as atypical for a male Western comic book lead as her muscular form. His interactions with the Morray servitors indicates an entirely different kind of experience to that of Eve, one where he is more unquestioningly in command.

Beyond the differences, however, are the similarities. The Lazaruses (Lazari? Lazarene? – something about the resurgent historicism of the setting has us wanting to employ bad Latinisms, but we will forbear until receiving further guidance) share both power and vulnerability. Eve’s emotional distance from her so-called blood, with whom she shares her life, is highlighted by her fellow-feeling with Joacquim, with whom she shares an affectionate kinship that feels far more authentic than their tense, formal loyalties to their own ‘families’.

Joacquim also experiences on of those other teenage dualities, the experience of new power and capability in your body, but also a growing sense that it is no longer your own, and is subject to requirements beyond your control. Joacquim’s cyberware provides him with all kinds of edges – he is faster, stronger, more durable, but coupled with this is the strict requirements of his special diet and the slight sense that he is somehow changing (or changed) into something other.

For all their posturing as plenipotentiaries/killing machines, there’s something delightfully pubescent about the line “Our families don’t understand” before the aborted kiss, echoing as it does that classic of star-crossed teenage romance, Romeo and Juliet, and the feeling of alienation and misunderstanding that has dogged every teenager since time immemorial. Joacquim’s slightly surly use of “us and them” positioning also references that “alone against the world” attitude common to teenage attachments. This underlines our sense that Eve’s feelings for Joacquim (and his for her) are one of the few things that are distinctly Eve’s, a small part of her inner life she has kept alive, untouched by her canny handlers, for year after year. This comparatively tame secret of her feelings for the rival Lazarus may well have set the stage for later, more serious, secret rebellions, including perhaps her growing dissatisfaction with her family’s treatment of the Waste and serf classes.

Uplift & Uplift

When Jonas calls the monitoring station to track Eve’s exact location, James is put in the impossible position of bending to Jonas’ threats or following Malcolm’s instructions. This test of loyalties is an exact analogy to the choice of poisoned chalices presented to the Morray Sergeant at the start of the issue – obey higher placed orders, or immediate ones. This contrast helps highlight the injustice of the fate of the otherwise unsympathetic Sergeant, and by obeying his standing orders from the head of the family, James has made the exact same decision. No wonder he looks nervous and deflated when he reports to Malcolm – he must be fully aware of the risk he has been forced to run.

James, of course, might be something of a special candidate, because as we’ve learnt from last issue, he and the Beth Carlyle appear to be more than simply mistress and servant. Her extreme reaction last time around makes more sense in the context of the honour culture we’re observing, as the loss of “dignity” in lowering herself to consort with a member of the serving classes appears only to be confirmed in exploring the wider context of master-servant relations in the new world.

Hence the duality of fitting into categories of both “status and authority” and “servitude and danger” implicit in the high ranking roles of the vassal class. People like James are contingently privileged but inherently vulnerable. We are able to pity and fear for them as much as we have to question the amorality of their collaboration with an unjust system. Indeed, while they are protagonists, these characters do make superb points of view, because they – the Sergeant and James and their ilk – best represent some of the social issues underpinning Lazarus, issues including how much the privileges of the social middle class blind them to broader concerns they face from a stronger oligarchy. We’re forced to ask “How much power have the Families been able to take, and how much has been ceded to them?”. As a piece of speculative fiction is in touch with the issues of today, this deserves to be front and centre in our thoughts.

Carlyle Dominion & Morray Dominion

It turns out the Morray’s power is, in essence, power. Real, temporal, technological power. Where the Carlyle forces were equipped with outfits reminiscent of cutting edge modern day military outfits and vehicles, the Morrays take that slight step into near-future super-soldiers as befits their position as military-industrial types. We noted from the previous iterations of the back matter than Malcolm Carlyle appeared to be the leading light in the field of genetics, and we sought to understand why he might be induced to share the incredibly value advancement that a Lazarus represents. It appears now that a combination of sold (or stolen) technology has been paired with other lines of research to allow a parallel evolution. Although “Lazarus” is a collective term, we have another implicit study in parallels and contradictions: the Lazarus may well represent the peak of human alteration achievable by each Family’s special subject, but each special subject may be effectively unique.

This reliance on military machines seems reflected even in Joacquim’s wistful discussion of implants and restrictions. Considered in the light of the Next Issue teaser, we suspect that even as Eve is the child of Carlyle medical-genetic prowess, Joacquim may well be more machine than man, showcasing the pinnacle of Morray milspec technology by having more cyberware than her bioware.

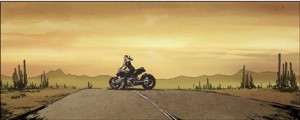

But in the game of houses, soft power is as critical as hard power and once again, the art exalts what would otherwise be blunt and perhaps forgettable background exposition. Through Santi’s fantastic colouring of the well-chosen landscapes of this issue, the dusty highways of the Morray dominions come off as bleak and despairing compared against the two Carlyle compounds. James is in a verdant compound taking its name from a tree; Johanna swims in a sapphire swimming pool surrounded by lush Californian greenery. Though we know from past issues that the Carlyles rule over their own dusty wastes, Michael and Santi have carefully used spacing and colour to highlight the relative lushness of Malcolm’s holdings, all the better to underscore the Edenic promise so essential to the meat of this week’s plot.

This though, yields up yet another study in contrasts – the easy honesty with which Joacquim appears to deal with Eve, and the degree of comfort he clearly has in interacting with his uncle is nicely reflected in those sparse, unfurnished landscapes. The Morrays are crude, violent, powerful and dangerous, but they’re also open in a way that the Carlyles, for all their refinement and pretty exteriors, simply aren’t. Given the assassination attempt that underscores the end of the issue, the distinction between the honest and the duplicitous takes on paramount importance, and using the landscapes to reflect this is a wise choice.

Jonah & Johanna

Here we find another confirmation of a pre-existing binary – the opening text tells us that Jonah and Johanna are not only siblings, but twins, and (let’s embrace those Game of Thrones references) more that just twins. (Brief aside: Can anyone remember when the term “twincest” first came into general use? The idea is a very, very old one, but the portmanteau doesn’t seem more than 10 – 15 years old). There is, of course, nothing like the use of twins to create a sense of doubling and duality (Everyone should go chase up a copy of Dead Ringers now, and then meet back here).

Jonah and Johanna are so close, at this point, that there is a lot to indicate we are looking at, as twins are commonly typed in media, “two halves”: acting with a common agenda, spurred by common desire, presenting a united front. The corresponding duality to all this symmetry, though, is the division between the pair. Jonah and Johanna appear to possess different competencies, strengths and ultimately agendas. Johanna is quick to accede to Jonah’s opinion of the situation on the surface, but displays a deeper concern about how he’s managing affairs overall and rapidly takes control through careful, considered methods. Jonah loses his temper constantly (five times in three issues), whereas Johanna, confronted with the same stimuli, remains perfectly calm. Jonah tries enthusiastically to carry out orders he likes, Johanna improvises rapidly when new information comes to hand.

Regardless of the quality of Johanna’s improvised plan (and we question its fundamental competence below), there is better sign of her political brilliance. It is telling that it is only Jonah who incriminates himself by calling James; only Jonah who dared attend the family conference to push the war agenda; only Jonah that the Morrays hang out to dry; and only Jonah that the teaser suggests will be in over his head. The word ‘patsy’ springs to mind.

Johanna’s ultimate two-facedness is best embodied in her interaction with faithful retainer Charles: she is polite, even pleasant, and then orders his execution behind his back as an afterthought. It’s a contrast to Jonah, who doubtless would’ve thrown yet another tantrum, possibly followed by a sloppy murder, if he’d known Charles was listening. This perhaps demonstrates a single piece of awareness which divides the competencies of the twins: Johanna is aware of the world around her, and Jonah lives inside his own head. This is particularly true as regards non-Family members: Jonah has come to see them as unpeople, as animals or objects to be handled or ignored. Like furniture. Johanna recognises Charles as a person with an independent agenda, a possible threat, and by inference we can assume that she also recognises that the Waste represent a population in crisis, capable of doing damage all on their own. What makes this insight all the more troubling is that Johanna is capable of recognising the exploitation and brutality implicit in her cultural paradigm, but is just as brutal (if not more so) than the entitled and culturally programmed Jonah.

Assuming that Johanna’s new plan of relying on the Malcolm to commit to a war he does not want based on a false assumption that the Morrays have killed Eve is not naive to the point of stupidity, it suggests the political status quo is such that the extraordinarily canny Malcolm will be forced to respond, rather than investigating or just even arbitrarily assigning blame. This implies a degree of pressure (in part presumably based on the honour culture we’ve otherwise talked about in this issue) to avenge slights, even where those slights are suspected to be caused by a third party. Dishonour cannot stand. This brings us to the most critical, and most subtle duality…

The Neo-Feudal Castle & The Negative Presence

Perhaps the largest piece to the puzzle provided this week has been the unveiling of the shape of the world. As a poli-sci and economics geek, David has been engaged in a number of debates about where the world of Lazarus falls on the divide between dystopian post-capitalist oligarchy of strongmen and an all-out neo-feudalism. With this issue, the debate can be, we think, settled.

Neo-feudalism describes not only the rise of domains of mass private property that are ‘gated’ through the force of arms of the privileged class and accessed by a captive populace possessing only conditional citizenship and rights (which is clearly Lazarus to a tee) but also the reemergence of those cultural and social trappings affiliated with a slightly alien culture of personal loyalty, social division and military exclusivity. As a system of governance, it is especially awful because it dresses up the brutal oppression with a return to legalistic and idealistic forms of discourse.

While this renaissance of disguised brutality has certainly been suggested through the first two issues (see the Family heraldry, Lazarus’ depiction as sword and shield and the resurgent open categorisation of captive slave populations as ‘serfs’), this portrayal is confirmed here with the introduction of guest rights (“She is our guest… and we will accord her the courtesy she is due”), formal emissaries (“I am Carlyle, Mister Morray. These are the words of my father.”) and royal prerogatives reflected in the grammar (“Caryle agrees”, “Morray agrees”).

This neo-feudal explication is all the more fascinating because of what is elided. Greg, a writer with a practiced ear for the dialogue of the dispossessed and disaffected and a track record of letting them speak for themselves in an authentic and moving fashion, has chosen, clearly deliberately, to leave the Waste spoken about and silent. Three issues in, the class of Waste remain not only without agency but almost entirely without voice.

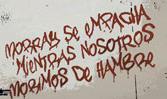

We say ‘almost’ because of the first panel of the issue, the graffiti on the Morray compound wall gives the Waste one crystal-clear rallying cry with a pedigree going back from the French Revolution through to the Hunger Games. In essence, the Waste’s only line has been as potent as it is irrefutable – ‘They feasted while we died of hunger!’

This, in itself, is perhaps the liveliest and most telling of dualities, the voiceless voice of the people, the vast majority whom we never see. In an issue brimming with duplications and contrasts, we are forcibly reminded of the underpinning social issues which drive Lazarus. For all the pomp and ceremony, spectacle and violence we have witnessed so far, these innately personal decisions both shape the path of innumerable lives, and are rendered into insignificance by them.

The power struggles that we see are incredibly compelling, and in a very real sense do change the fate of what passes for nations in the world of Lazarus. But nothing demonstrates how truly petty the struggle for power amongst already privileged oligarchs is than forcing us to consider in absentia, the rest of the population. What does it matter who holds the top seat in the garden, when everyone else is left outside to starve?

A large part of the reason we love Lazarus so much is that there is a fine tradition of literary science fiction which places the problems of our world front and centre, by metaphorical extrapolation, by exaggeration or by appeal to consequences. Though there are many science fiction comic books, many focus primarily on the kinetic adventure, and ignore the opportunity to truly look at issues that plague us every day. Lazarus’ greatest duality is that it never shies away from placing those social issues front and centre, but still crafts a compelling thriller without abandoning or suborning them. There are two narratives in Lazarus, a conspiracy thriller and a portrait of society in collapse, and Issue #3 ably highlights that in serving both, you cause them to serve each other.

September 6, 2013

In the time between writing this and it being published, a Tumblr clarification was issued. The plural is “Lazari”.

http://familycarlyle.tumblr.com/post/60113622480/style-notes