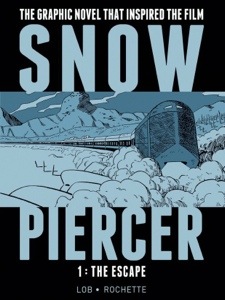

Titan Comics, also in the news this week for getting the license to produce Doctor Who comics, is publishing an English translation of La Transperceneige. You may know the story better as Snowpiercer, if you have been following the news about the Korean science fiction flick which has had 20 minutes of cuts and a stalled American release thanks to Harvey Weinstein. Originally written in French by Jacques Lob and illustrated by Jean-Marc Rochette in 1982, the story is undergoing a revival in world culture through Bong Joon-Ho’s epic movie which has finally led to this first English language translation, volume one of which, The Escape, comes out January 28th.

You can click on this hyperlink to watch the international trailer, but here is a capsule summary. In the wake of an ecocatastrophe, a new ice age, the extinction of humanity is stalled by an immense train in which resides the thousands that are left. And this is no ordinary train. You’ve certainly heard of a bullet train; well, this is a perpetual motion engine pleasure train of 1001 cars called Snowpiercer, that was originally a venal paradise of prostitution. These are no noble remnants; instead, the survivors of humanity are also the dregs of it.

Animal Farm is the first book you think of when you think of allegorical class warfare, but Snowpiercer makes its point as well, and it’s not the one you think it is making. Just as in Lord of the Flies, when anarchy ensues the worldwide wipeout, a new class structure develops which mimics the “vertically horizontal” strata of the train. Much has been made of the class structure in other reviews on this story—with the Occupy movement not being entirely passé the temptation must be too great—but what most other reviewers have missed is that all the classes are morally inferior. True, the upper classes snort drugs and rut in luxurious first class staterooms, while the lower classes in their sardine squalor pack the cabooses, but all the classes on this train are more like Dante’s circles of Hell than some Marxist revolution engine. All social classes indulge every hedonism that they can get away with. The poor may eat rodentia, but after 900 cars of Proloff’s journey through Snowpiecer we see that the elite are dining on mere rabbit. Its hero Proloff is no activist, but instead enacts his own will to power by leaving the back of the train and indulges his self-help fantasies by literally getting ahead of his station. The irony is that he is also an agent of change by perhaps being a carrier of a virulent disease that tears a swath through the cars that he passes through.

Proloff is a fairly straightforward character, no mythic hero but a running man. The book’s main literary conundrum is the problem of what should the reader think of Adeline. Adeline, Proloff’s foil and the book’s deuteragonist, is a stock middle-class activist. If she is the “excluded middle” in Snowpiercer’s dialectic on class, that third alternative is a shallow one there only to add the one dimensional thoughts on social justice of which she is a proponent. Supposed to be the compassionate antidote to the paranoia of the elite which believes opening up the tail of the train will allow the migration of diseases, her idealism is shown starkly as naïveté when a disease does indeed follow Proloff through the train. It is probable if she had not been thrown into quarantine and forced to journey to the front of the train, her final pages would have come a lot sooner and her contribution to the story would have been a lot smaller. If we are to believe, as so many do, that this is a book about class mechanics, how does Adleine fit into this formula? Does she represent activism as futile, as weak, as being unable to implement change in a population that is chiefly interested in fulfilling its Maslowian needs, then its venal desires, and only then has afterthoughts of idealism? Afterthoughts may not be the right word here: resentment of idealism is probably more accurate, if we quote the words of one whore on the train : “Hey! You gonna carry on much longer with this boring preachy shit?! Some of us are trying to fuck here!” These are the words not of someone looking to be helped by social activism, but of someone happy in the Darwinian space of Snowpiercer, like one of the unrepentant residents of Dante’s second circle of hell, Lust. And, if her flatness as a character indicates that she is the reader’s audience surrogate, if we are invited to identify with her are we also being invited to be complicit, so that readership becomes voyeurism?

No, don’t be confused by the apparent message of Snowpiercer 1 : The Escape, because it is a white rabbit; the authors know that they are writing not an allegory on class war, but a fable on human nature; not agitprop, but science fiction. It is a wonderful graphic novel indeed, not only in its attempts to deceive the reader that there is a moral therein, but also in its elaborate construction of a society in microcosm and in its concealment of its more metaphysical argument that human nature is wicked and only extinction is waiting for us, and only, perhaps, our technological toys might survive us.